There is a growing interest in the socio-economic contribution of the creative economy. It is spurred by the technological and digital transformation happening worldwide at an unprecedented rate and the increasing shift from an industrial to a knowledge-based economy where creativity and innovation are becoming critical.

The commercial and cultural values of creative industries have become instrumental in driving entrepreneurship and innovation. They offer new economic opportunities and generate income through trade and intellectual property rights. Supported by a dynamic value chain composed of small and independent enterprises, non- profits, and professionals, the creative industry can empower local communities and foster ownership which is critical to inclusive and sustainable growth.

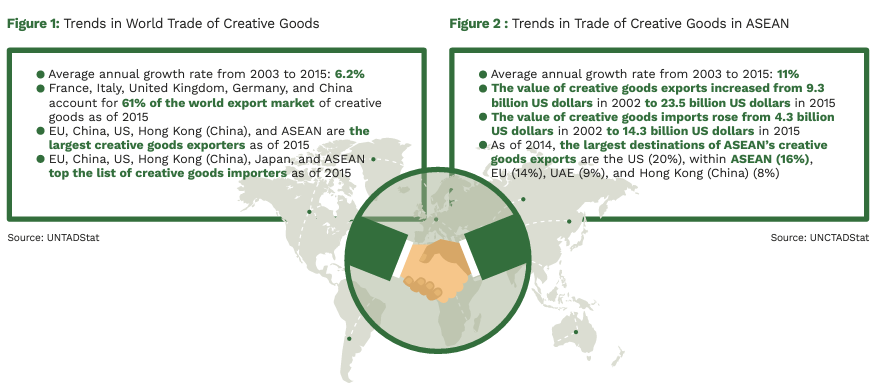

According to the global database of United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, 2021), world trade in creative goods reached 964 billion US dollars in 2015, more than double the value in 2002 (436 billion US dollars). ASEAN is becoming an important player in the export and import of creative goods. (Figures 2 and 3)

For the past decade, digital technology has played a significant role in the economy and affected the trade structure, including the creative industries. ASEAN’s export structure of creative goods has relied significantly on the design sector, constituting three quarters of the total creative goods exports.

Despite its strong dominance, the design sector’s export share has been diminishing over time. The publishing sector’s contribution also showed a similar drop. In contrast, the export share of the audiovisual and new media sectors has been rising steadily. (Figure 3)

A closer look at these figures reveals a more complicated story. In the region, the development of the creative industries is uneven, with the largest share of the ASEAN trade in creative goods coming from Singapore. Thailand, Malaysia, Viet Nam, and Indonesia to a certain extent are supporting the ASEAN trade in creative goods, particularly in terms of exports, while the rest of the countries’ contributions are constant albeit modest. Apart from Singapore, a majority of ASEAN members “still belong to the factor- and efficiencydriven categories of development where creativity and innovation play a minor role in their development” (Puutio 2016; World Economic Forum 2013).

A combination of factors can hinder the growth of the creative sector, such as the lack of policies that support the ecosystem, access to financing and f inancial sustainability, the nature of creative work, and the valuation of creativity, among others. The increase in the digital adoption in many sectors has created new forms of social and economic opportunities, especially for small and medium-sized cultural and creative enterprises. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has resulted in the loss of income and livelihoods for several key industries within the creative economy.

Drawing from the framework of government interventions across the creative economy value chain by the Boston Consulting Group, we look at four factors that are necessary to address to boost the creative economy in the region: policy building, sustainable financing, digital readiness, and clustering.

Policy Building

Most, if not all, ASEAN countries have included the creative economy in their national development strategies. As a result, they have agencies and institutions dedicated to fostering and promoting creative industries. These agencies can act as one-stop shops for small, medium creative enterprises (SMCEs), providing them information on finance, opportunities, incentives, among others. For example, in Brunei Darussalam, according to Brunei Economic Development Board (BEDB) (2020), the government sets five priority business clusters, namely halal food, business services, tourism, downstream oil and gas, and technology and creative industry, while emphasising the importance of the financial services sector that will help achieve its long- term national development plan.

In Cambodia, while the cultural industry has constantly been growing over time since the first adoption of its national cultural policy in 2014, the advancement of the creative industry still lags because of inconsistent government support.

Indonesia had recognised the significance of the creative economy since 2008 when it outlined the 2009-2015 Creative Economic Development Plan. It aimed to build a creative industry investment environment, develop human capital, and promote innovation (Simatupang, Rustiadi, and Situmorang, 2012).

The creative industries in Lao PDR and Myanmar are still at the initial stages, with no specific government policies in place.

Malaysia has advocated for the creative industries through policies and programmes that prompt infrastructure and market-based improvements, e.g. streamlining intellectual property, enhancing human capital development, and penetrating international markets. These initiatives are based on the country’s National Creative Industry Policy or Dasar Industri Kreatif Negara (DIKN) issued in 2009.

The Philippines is a latecomer in promoting the creative industries among the ASEAN-5. However, the Creative Economy Council of the Philippines (CECP) has set an ambitious goal of making the Philippines’ creative industries number one in ASEAN and among the top five creative economies in the Asia Pacific by 2030, in size and competitiveness.

Singapore’s creative industries have been taking the lead in the ASEAN region. As early as the 1980s, the government’s forward-looking policies recognised the importance of the industries as part of the tourism sector. The creative sector has since established its own space and value through well-crafted policies, and strategies such as the National Arts Council (NAC)’s “A Global City for the Arts” in 1995, and the Ministry of Information, Communications, and the Arts (MICA)’s “Creative Industries Development Strategy (CIDS)” that was in accordance with the Economic Review Committee’s vision in 2001.

The development of creative, cultural, and high value services (part of the creative industry) is one of the technological and industrial goals described in the “Thailand 4.0” strategy (Korwatanasakul, 2019). The government established the Thailand Creative Economy Agency (TCEA) in 2011 which aims to combine creativity, innovation, and cultural assets to deliver higher value products and services and upgrade the industry into a creative hub of ASEAN. The Creative Economy Plan coupled with the Creative Economy Fund was set up to meet these goals.

Viet Nam considers creative industries as part of the cultural industries. In 2016, it adopted National Strategy for the Development of Cultural Industries and set a conservative target for the contribution of the cultural industries to the national GDP at 7 per cent by 2030 (Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism of Viet Nam, 2016).

Sustainable Financing

Financing for SMCEs historically has been fraught with challenges. It is well documented that in general, lending to SMEs poses higher risks compared to large corporations (Dietsch and Petey, 2004; Altman and Sabato, 2007). There is compounded risk aversion among lenders when it comes to SMCEs. Borin, Donato, and Sinapi (2018) note that access to finance has been considered a major hindrance to entrepreneurship development in the cultural and creative fields.

When it comes to sustainable financing, SMCEs in ASEAN continue to rely on a mix of private and public financing. This is because of two things; first the general perception of SMEs being high-risk for many private financing institutions, and second, SMCEs specifically in culture and arts often rely on personal f inancing and donations. SMCEs in the culture and arts sector, therefore are more likely to self-exclude financially. In these instances, governments can give support by bridging the gap between SMCEs and the private sector. We also found that States with coherent and consolidated national strategies are able to provide more funding opportunities, whether it be purely public, or mixed financing.

For example, in Indonesia the defunct BEKRAF launched the Government Incentive Assistance (BIP) programme to improve the financial access of f irms investing in the digital application, game development, and culinary sub- sectors (Wreksono, 2017). Creative economy businesses in Indonesia also have NextIcorn, a platform launched by the government and private sector to fund start-ups.

In Malaysia, the government subsidises the country’s cartoon and animation industry funding offers worth 2.7 million Malaysian ringgit (equivalent to 649,000 US dollars), through the Malaysian National Film Development Corporation (Finas), for purchasing content from animation companies (The Sun Daily, 2018). Malaysia also has a number of grants under the Cradle Investment programme.

Singapore, on the other hand, provides grants to artists through the National Arts Council. While there are no specific measures towards SMEs in the creative industry, the government has committed 2 billion Singapore dollars for SME loans. Moreover, various local and international financial sources are available for SMEs.

Digital Readiness

ASEAN’s level of digital connectivity, such as internet use, mobile cellular subscriptions, and electronic and mobile commerce (e-commerce and m-commerce) penetration is considerably high, comparable to developed economies. In 2019, ASEAN’s average rate of individuals using the Internet is approximately 58 per cent of population, while, on average, there are 134 mobile cellular subscriptions per 100 people in the region (World Bank, 2021). Figure 4 shows the high penetration of e-commerce and m-commerce among ASEAN countries, with the annual growth of 40 per cent (ASEAN Secretariat, 2019).

The region hosts the fastest growing digital startups, including e-commerce platforms such as Lazada, Shopee, Grab, and Gojek. Such platforms allow entrepreneurs to reach a wider market. The use of digital financial services in the region is on the rise, making it easier for creative entrepreneurs to sell and receive payments for their goods and services. Nevertheless digital readiness remains uneven across the region, even as digital connectivity continues to improve. Digital readiness refers not just to infrastructure but to skills and adoption.

Clustering

Considerable research has been conducted on the geographic clustering of creative industries to drive innovation and growth. For example, in Western Europe, North America, and Australia where much of the research has been done, “clustering” has shown to contribute to the revitalisation of inner- city neighbourhoods and rural areas (Fleischmann et al, 2017). Establishing strong networks of creative industries can increase visibility and attractiveness to investors. Moreover, creative industry networks can provide the necessary assurances for financial institutions, increase SMCEs’ credibility and potential access to markets, and subvert funders’ perceptions that investing in SMCEs is uncertain and risky. Networks can give birth to collaborations that assure the spread of risk and cost-sharing. In addition, the literature points to “knowledge spillovers,” where knowledge flow between and among enterprises through collaboration and observation (Fleischmann et al, 2017).

In the ASEAN region, clustering is also seemingly lopsided, States with consolidated national strategies are supporting the development of creative hubs. Data are not consolidated, however, as in some cases, creative hubs are still closely linked with the sprouting of coworking spaces. Support is still seen to be coming from external entities rather than from within. For example, through its Hubs for Good programme, the British Council works with creative hubs in the region (British Council, 2019).

Creative hubs are finding more support from the private sector, philanthropic networks, and venture capitalists. Impact investing is also a source of funding for creative hubs because of the inherent nature of creative industries, seeking both for- profit and social impact. More and more, creative makers, creative hubs, and spaces are utilising social media platforms to network, promote, and market their activities. The popularity of social media platforms and increased digital connectivity in the region have allowed creative entrepreneurs access a broader group of audiences and potential markets.

Future Growth Prospects

The developments in the creative economy in the region remain uneven. The countries considered to be ahead have adopted one of two strategies: they included the creative economy in national development strategies, or formulated specific strategies towards developing the creative economy. On the other hand, countries that are considered lagging are in the early stages of developing a creative economy, and in some cases still have a limited discussion on what constitutes a creative economy.

The lack of consensus on the definitions of the creative economy may be a hurdle for many countries, even beyond the ASEAN region, to craft policies to support the creative ecosystem. Strong policies act as frameworks from which developments in the creative economy can proceed. Policies that support the creative ecosystem are necessary for entrepreneurs and actors to thrive and grow.

While policies and the digital and technological infrastructure have already been set in some countries, another consideration involves the processes through which policy responds. Governments need to be able to engage with organisations that are “micro, fluid, disaggregated— in many senses ‘dis-organised’” (Holden, 2007).

Technological and digital innovations, while providing resources, can cause challenges to governments gearing up to foster the creative economy. Issues of widening the digital divide notwithstanding, capacity building tailored to the needs of SMCEs to improve their readiness and awareness of the various schemes, funding sources, and resources that they can tap.

Fostering the creative economy requires creativity. It demands the exploration of “fresh set of institutional questions and responses, not just the straightforward application of models that have worked at other times and in other places” (Holden, 2007).

References:

The complete list of references is available at the following link: https://docs.google.com/document/d/ 1-ZoOriLL1guR6IkCC7adkUIlT2vbEHRg/ edit?usp=sharing&ouid=1086875421 88381018676&rtpof=true&sd=true