Women in the informal economy are not a homogenous group. At the same time, population ageing is not gender-neutral. The population in Southeast Asia is ageing, and due to their longer life expectancies, women form the majority of the older persons in the region. Given this demographic trend, there is important work to understand the intersections of ageing, gender, and livelihoods. However, this subject has received relatively little coverage in existing studies to address the root causes of gender inequalities and cleavages in the informal economy.

Women in the informal economy are not a homogenous group. At the same time, population ageing is not gender-neutral. The population in Southeast Asia is ageing, and due to their longer life expectancies, women form the majority of the older persons in the region. Given this demographic trend, there is important work to understand the intersections of ageing, gender, and livelihoods. However, this subject has received relatively little coverage in existing studies to address the root causes of gender inequalities and cleavages in the informal economy.

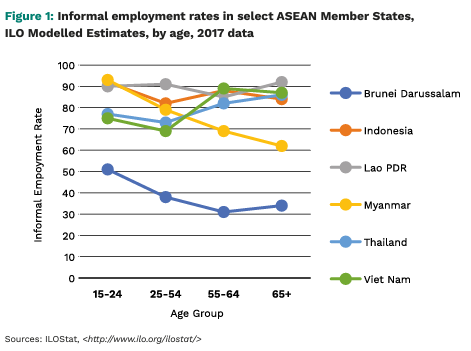

Older women in informal employment in Southeast Asia Globally, levels of informal employment are higher amongst older workers. Similarly, in Southeast Asia, the level of informality is higher among older people (65 years old and older), particularly in Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Thailand, and Viet Nam (Figure 1).

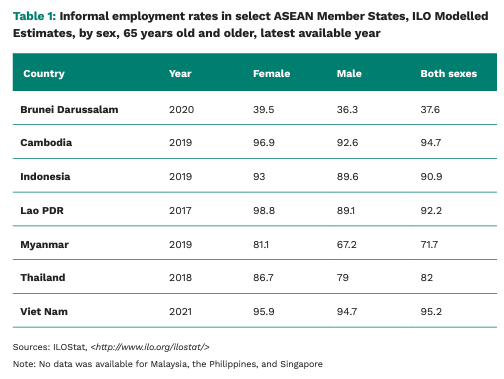

Older women in the region are more affected by informality than older men, with rates surpassing more than 95 per cent in Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Viet Nam (see Table 1). According to the ILO (2019), this is a sign of vulnerability as it shows older people, particularly women, having difficulties finding formal jobs due to their age, while the lack of old-age income security forces them into informal employment arrangements.

Among older women, the diverse motivations for continuing to work include economic necessity, personal preference, social norms, and broader gendered inequalities (Samuels, et al., 2018). Based on the latest UN report on human rights of older women, working in older age has both advantages and disadvantages for older women (Mahler, 2021). On the positive side, work can increase financial independence, provide a sense of fulfilment and greater status within a household, and can give cognitive advantages. However, on the other hand, it can negatively affect older women’s physical and mental health due to poor working conditions, exposure to discrimination and abuse, and cause them added stress from multiple responsibilities at work and at home (Mahler, 2021).

Within the informal economy, older women workers often experience multiple forms of discrimination based on both their gender and their age. This includes ageism, vulnerability to exploitation, lower incomes, a gender pay gap, poor working conditions, and income insecurity (Gorman, et al., 2010). Furthermore, older workers are excluded from accessing credit schemes, limiting their potential to grow their businesses and trapping them in lower-paid work. Since most retraining and redeployment schemes are generally targeted at younger people, older workers have limited opportunities to improve their skills and educational level in later life (Samuels, et al., 2018).

The COVID-19 crisis also highlighted the precariousness of older workers’ livelihoods. Evidence from WIEGO’s COVID-19 Crisis and Informal Economy Study—a multi-city longitudinal study that assesses the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on specific occupational groups of informal workers and their households, with a focus on domestic workers, home-based workers, street vendors, and waste pickers—revealed that when the pandemic hit, the earnings of older informal workers fell to a greater extent than those of their younger counterparts. At the same time, their income recovery has been slower. This was observed to have affected slightly more older women than men.

Contributing to this situation is that many women do not have old-age income security through a public pension mechanism. The cumulative disadvantages of precarious and informal work and regular breaks from paid work to provide care, make it difficult for women to contribute to pension funds, often resulting in lower pensions for women (Mahler, 2021). In South-Eastern Asia, only a third (31.5 per cent) of persons aged 60 and older receive an old-age pension (ASEAN, 2020). While coverage rates vary among countries in the region, women are consistently disadvantaged; effective coverage (i.e., the proportion of older persons who receive pension benefits) of women in contributory schemes is always lower than men. For example, under the contributory social security scheme (SSS) in the Philippines, the proportion of female old-age pension beneficiaries (29 per cent) is almost half that of men (53.2 per cent) (ASEAN, 2020). In Indonesia, older men are three to five times more likely to receive a pension than older women (2007 Indonesia Family Life Survey, as cited in Harding, et al., 2018). This gender gap in old-age pension coverage highlights further inequalities within countries in the receipt of old-age pensions.

The non-contributory or social pension has closed the gender gap in old-age pension coverage but does not go far enough. For example, in Thailand, 84.6 per cent of women above retirement age receive the Old Age Allowance compared to 77.9 per cent of men (Harding, et al., 2018). However, only six out of 10 ASEAN Member States are implementing non-contributory pensions, with only Brunei Darussalam and Thailand having near-universal coverage. Recently, Myanmar has introduced a tax-funded (non-contributory) scheme for persons older than 90 while Singapore has introduced matched savings for the Central Provident Funds members, which will benefit more older women.

WIEGO social protection strategy in Southeast Asia for older workers WIEGO recognises the significant contributions of older men and women in informal employment and their challenges in fulfilling their right to work and access the labour market. As a response, WIEGO Social Protection Programme launched a pillar of work on Income Security for Older Workers which understands older informal workers as people who are contributing to household incomes and to care work, rather than as “the unproductive elderly.”

As many older informal workers in the region cannot afford to stop working, WIEGO advocates at least a basic pension for older women and men, which would enable the choice to continue working or not, and the level of intensity of the work in which they do engage. Social pensions can also be an important mechanism for providing relief during times of crisis. As the pandemic showed, older workers living in countries with social pensions in place were more able to receive timely income support (Alfers, et al., 2021).

Particularly for older women and men who want to remain economically active, it is critical that the decent work agenda extends to them, too—providing greater opportunities, tackling discrimination, extending healthcare (including in the workplace), and improving representation for older people in processes of change.

In Southeast Asia, WIEGO works closely with membership-based organisations (MBOs) in the region, such as the HomeNet Southeast Asia, Streetnet International, and International Domestic Worker Federation (IDWF), supporting their advocacy toward comprehensive, inclusive, and gender-responsive social protection for workers in the informal economy. During the pandemic, HomeNet Thailand helped its older members overcome digital barriers to access by ensuring that they had the support of younger family members in filling up the online application portal for emergency relief. Through our Social Protection training in the Philippines, we were able to link HomeNet Philippines to a local organisation advocating for a universal social pension. Very recently, HomeNet Southeast Asia developed its social protection strategy with income security of older workers as one of the priorities.

WIEGO and MBOs partners intend to work more collaboratively with the Senior Labour Officials Meeting (SLOM) and the ASEAN Secretariat in bridging the research gaps in gender, age, and informal work and in determining effective strategies for expanding the social protection of workers in the informal economy, particularly promoting decent work and income security for older informal workers.

About WIEGO

Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) is a global network focused on empowering the working poor, especially women, in the informal economy to secure their livelihoods. We believe all workers should have equal economic opportunities, rights, protection and voice. WIEGO promotes change by improving statistics and expanding knowledge on the informal economy, building networks and capacity among informal worker organizations and, jointly with the networks and organizations, influencing local, national and international policies. Visit www.wiego.org.