Unpacking unpaid care and domestic work

The provision of care work that is largely unremunerated continues to fall on the shoulders of women and girls. Globally, women spend an average of over 250 minutes each day performing unpaid care work. This is thrice the amount of time men spend (UN DESA, 2023). It is estimated that 21.7 per cent of working-age women, or around 606 million, perform unpaid care work on a full-time basis, in contrast to 1.5 per cent of men or 41 million (ILO, 2019; ASEAN and UNESCAP, 2021).

The world is facing rapid population ageing, with some of the fastest ones found in ASEAN. Globally, by 2050, the number of persons aged 65 years or older is expected to double, exceeding 1.6 billion. While longevity is a huge development gain, the provision of long-term care remains unpaid and falls on family members. A closer look at the data reveals that women live longer lives than their male counterparts. In their old age, women provide more care for family members: they play critical roles in providing long-term care, and “bear the brunt of deficiencies as they comprise the majority of both care recipients and paid and unpaid care givers,” especially those with disabilities. Current estimates indicate that globally, women contribute 71 per cent of the estimated time allotted to unpaid care for people with dementia. And such allocation increases to 80 per cent in low-income countries (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2018; UN DESA, 2023).

External shocks such as disasters and pandemics increase the amount of unpaid care and domestic work assumed by women and girls. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 30 per cent of women noted an increase in domestic work, compared with 16 per cent for men, in the ASEAN Member States (UN Women and ASEAN, 2021).

Rural women, in particular, rely more on natural resources for their livelihoods than men do. Climate change-related disasters, such as storms, floods, droughts, and earthquakes, adversely affect women’s productive work—agricultural production and off-farm productive activities—and unpaid work such as collecting water and firewood.

The provision of care, including unpaid care and domestic work, affect the caregivers themselves. Like paid workers, they experience significant physical and mental stress. For example, older women providing care may face more challenges when caring for older relatives and other family members (UN DESA, 2023).

Social inequality is also observed in care work. Women and girls living in poverty are more vulnerable because they spend more time on unpaid care and domestic work than their wealthier counterparts. They have little or no capacity to pay for domestic help or to buy time- and labour-saving devices.

Rural women spend more time in unpaid care and domestic work than women in urban areas. And in developing countries, large portions of the urban population live in slums with limited or no access to safe water and decent housing. These cause women and girls in urban slums “to be especially vulnerable as they struggle with water collection and cooking with harmful fuels” (UN Women and ASEAN, 2021).

The value of unpaid care work is substantial. UN DESA estimates that around 16.4 billion hours spent on unpaid care work every day is equivalent to 2 billion people working eight hours per day with no remuneration (Scheil-Adlung, 2015; UN DESA, 2023). On the other hand, Oxfam (2020) estimates that unpaid care and domestic work contribute at least 10.8 trillion US dollars a year to the global economy.

The study, Addressing Unpaid Care Work in ASEAN, indicates that due to the region’s economic growth, care infrastructure, such as safe water, sanitation, transportation, and food, is now more available, especially in urban areas. However, countries with large rural populations still have inadequate access to care infrastructure compared with their urban counterparts.

The study observed progress in certain countries on the coverage of basic benefits in the formal sector. But, since women are overrepresented in the informal sector, there is a need to shift the provision of care policies to benefit the informal sector workforce. And although the region has social protection measures, a closer look reveals that countries can better address the care-differentiated needs of women in care-related social protection programmes. Moreover, population ageing and the resulting intensification of women’s care work make it essential to revisit policies and programmes on care services for both paid and unpaid provisions of care.

Unpaid carers have limited access to social protection that can lift them out of poverty and emergencies. This lack of protection reinforces the idea that unpaid care work can be invisible. It is an urgent problem that must be addressed as it leaves vulnerable and at-risk people, like unpaid carers, grappling with poverty and economic dependence. With an average social protection expenditure at 5.3 per cent of aggregate GDP and an average expenditure per intended beneficiary of 4.0 per cent of GDP per capita in 2015 across Asia (ADB, 2019), there is still much work to do as the social protection landscape has changed dramatically post-COVID-19.

ASEAN Comprehensive Framework on Care Economy

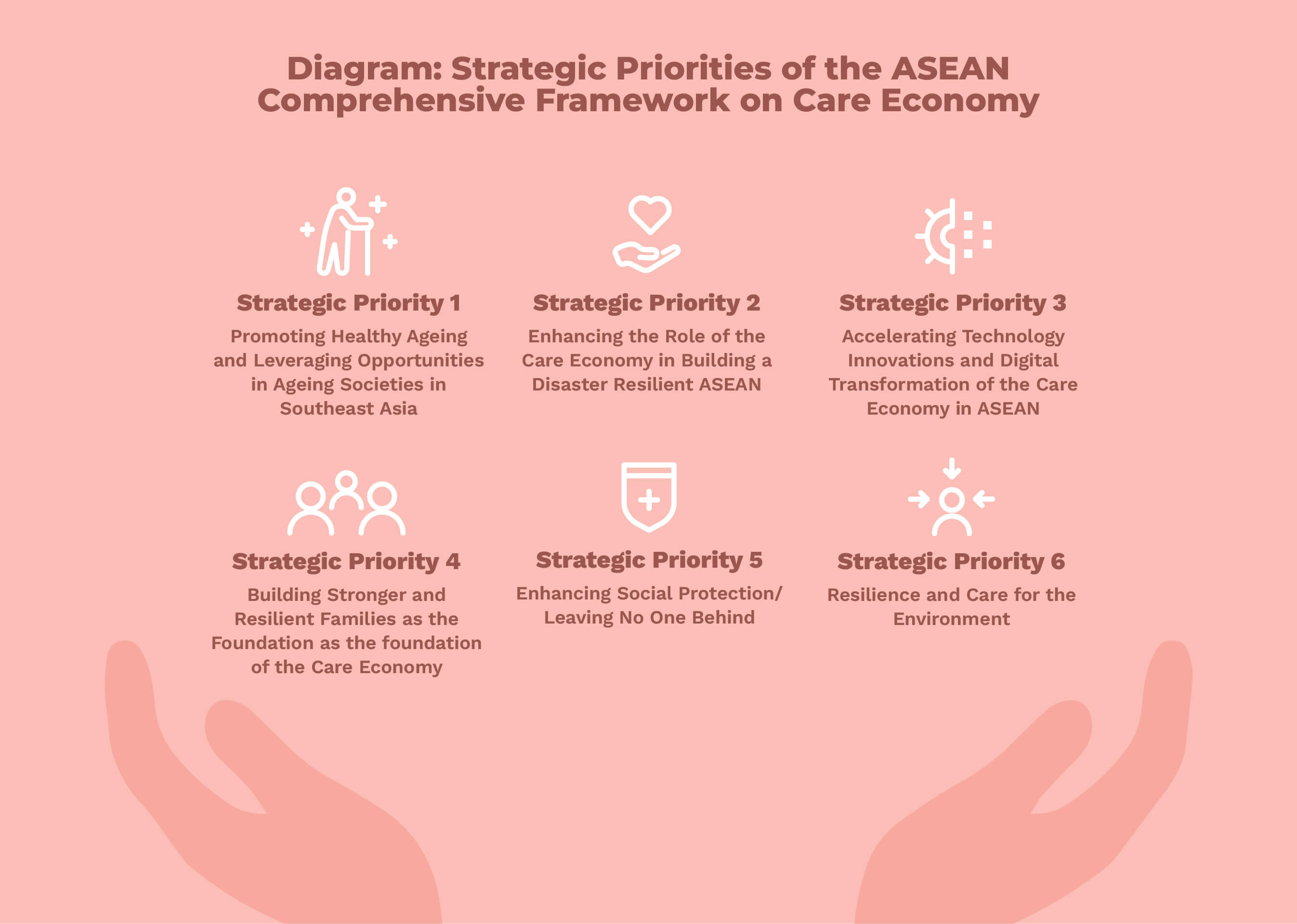

Adopted by the ASEAN Leaders in October 2021, the framework places “care” at the centre of public policy, with initiatives on care and care work contributing to “sustaining, continuing and repairing the world we live in.” It utilises a whole-of-ASEAN approach to promote care economy in the region as it outlines strategic priorities and relevant sectoral initiatives to realise an ASEAN Care Economy.

A key feature of the framework is its recognition that care work permeates various settings and formal and informal economies. It looks at care work and the economy across ASEAN labour markets and their increasing demand for child care, care for the older persons, and the concomitant reforms in care policies, infrastructure and services. More importantly, the framework broadens the scope of the “care economy” to encompass care work—both paid and unpaid—and other related areas. For instance, “paid care work” includes public services, elder care, and domestic work, while “unpaid care work” covers care in “familial, community, or other types of relationships.” The other related areas cover “reskilling and upskilling employability in sectors that are crucial in the context of a care economy, embracing of new technologies towards lifelong learning; hospitality (tourism) in terms of the changing demographic; development of creative industry and encouraging social entrepreneurship especially for the benefit of the vulnerable groups; as well as smart cities to smart homes, etc.”

In sum, valuing care work, particularly unpaid care and domestic work, towards building an ASEAN Care Economy, needs to be guided by the 4R approach: Recognise, Reduce, Redistribute, and Represent.

- Recognise unpaid care work as work that has value and raise the visibility of its contributions to the economy and society as a whole. Such recognition needs to be reflected in government policies and budgetary allocations, and through the generation and collection of statistical data to inform policies and programmes.

- Reduce the number of hours spent on unpaid care work by ensuring and enhancing access to care support infrastructures and services.

- Redistribute unpaid care work equitably within the household and, broadly, in the community, public institutions and the private sector

- Represent providers of care, particularly women and girls, and amplify their voices in the formulation, implementation and evaluation of policies and programmes on care work through meaningful and substantive participation in decision-making processes.

An enabling environment that lets women and girls thrive and prosper and empowers the most vulnerable groups, including persons with disabilities and older persons, is essential to building a resilient care economy. It also requires strengthening human capacities, especially the social service workforce, to implement strategic and catalytic interventions for these groups. The interventions include effective social welfare and social protection measures that go beyond charity to reach the people who need them most for decent living.