The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2010), which has been instrumental in promoting and analysing creative economies all over the world through its Creative Economy Program, described the creative economy (CE) as “an evolving concept based on creative assets potentially generating economic growth and development.”

In Thailand, this concept has been proposed since the early 2000s as an engine of growth that could strengthen its international competitiveness. Almost two decades have passed, and Thailand still struggles to contextualise this concept in the Thai setting, manage the tension between economic and cultural values, and develop policies that recognise all stakeholders and allow them to contribute to sustainable development. For a country rich in culture and creative assets but stuck in the middle-income trap, there is no question that CE would bring a host of benefits to Thailand and its people. There have been many attempts to boost the economy through activities based on creativity and innovation, but the successful implementation of CE theories and practices is far from being realised.

Government Initiatives and Policies Related to the Creative Economy and Creative Industries

In Thailand, the concept of creative economy was first discussed when Thaksin Shinawatra was the Prime Minister of Thailand and developed during the premierships of Abhisit Vejjajiva and Yingluck Shinawatra. In 2009, the Thai government’s “Creative Thailand Policy” was initiated with an aim to make Thailand the creative industrial hub of ASEAN. Several government agencies, such as the Software Industry Promotion Agency (SIPA) (which became the Digital Economy Promotion Agency or DEPA in 2017), the Office of Knowledge Management and Development (OKMD), and Thailand Creative and Design Center (TCDC), were the key actors in advancing the idea of the CE in Thailand at the time. However, when a military coup took place in May 2014, all projects related to the creative economy were subsequently suspended. The focus of the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), the military junta which governed Thailand until July 2019, has been on the promotion of a digital economy, which could be seen as a way for the new government to distinguish itself from the policies created by earlier governments.

The focus on creative industries reappeared when the Creative Economy Agency (CEA) was reestablished in August 2018 by the Office of the Prime Minister, under the leadership of Prayuth Chan-O-Cha. The CEA aims to drive the creative economy policy forward through collaboration with public and private sectors. The first CEA Forum was held one year later to serve as a platform for knowledge and experience exchange regarding the development of the creative economy, including the creative economy policymaking, the formation of creative spaces for businesses and communities, and the utilisation of creativity as a means to gain a competitive advantage (CEA, 2019). In the past two and a half years, CEA has successfully initiated the Thailand Creative District Network (TCDN), which connects public authorities, the private sector, and civil society to develop creative spaces in municipalities all over Thailand.

The CEA was also active in providing research and information to the city authorities of Bangkok and Sukhothai in the application of UNESCO Creative Cities. In 2019, the two cities were designated “Creative City of Design” and “Creative City of Crafts and Folk Art,” respectively. CEA’s Bangkok Design Week, considered a growth engine for the creative industries, has been organised annually since 2018 and draws approximately 400,000 visitors each time. Moreover, there are a variety of smaller projects throughout the year, such as “CEA Online Academy,” an open online learning platform with creative skills courses, and “CEA Vaccine,” in which CEA commissioned over 300 artists and provided consultation and assistance to small and medium businesses in the creative industries (CEA, 2021).

Key Actors in Thailand’s Creative Economy

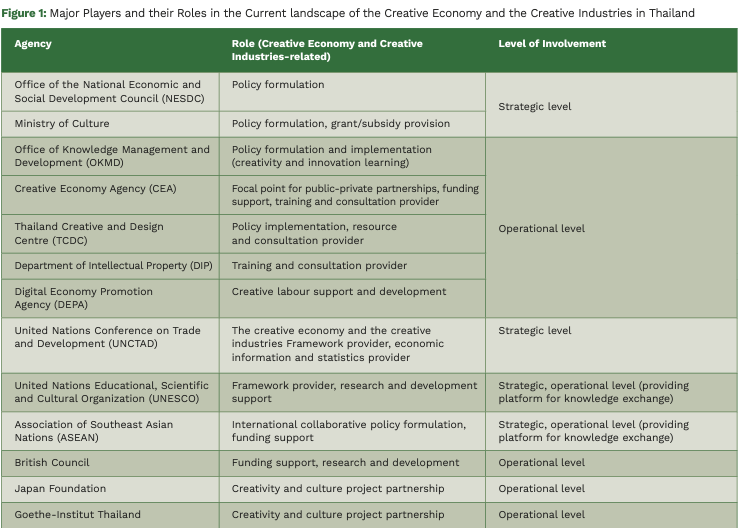

The Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC) is responsible for policy development and is one of the key actors at a strategic level in the development of the creative economy and the creative industries. Figure 1 below shows all of the major players and their roles in the current landscape of the creative economy and the creative industries in Thailand. This list is not exhaustive and only includes some of the most prominent agencies whose work is directly related to the creative economy and the creative industries.

Challenges Faced by Thailand’s Creative Industries

In the 11th National Economic and Social Development Plan (2012-2016), NESDC identified four major groups and 15 industries within the creative economy, following UNCTAD’s classification. The groups were renamed, and their industries reshuffled in 2020 as follows:

i. Creative originals: Thai crafts, music, performing arts, and visual arts

ii. Creative content/media: Film and video, broadcasting, publishing, and software

iii. Creative services: Advertising, design, and architecture

iv. Creative goods/products: The fashion industry

v. Related industries: Thai food, traditional medicine, and cultural tourism (CEA, 2021)

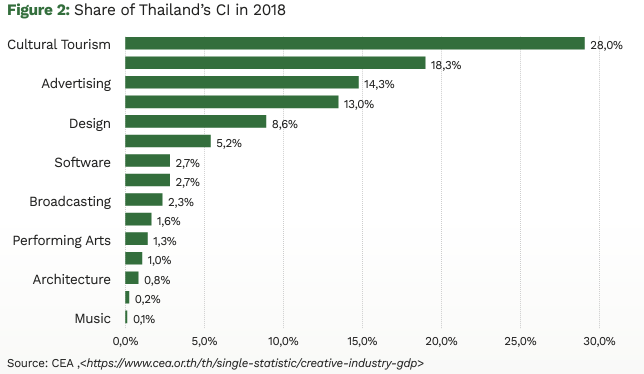

According to CEA, the creative industries contributed 8.93 per cent to Thailand’s GDP in 2018 (0.8 per cent less than in 2015 at 9.1 per cent of GDP and 3.07 per cent less than in 2009 at 12 per cent of GDP). This contribution is valued at 46.4 billion US dollars. Figure 2 indicates the economic contribution of specific industries. In terms of growth, the only industry with an increase in its contribution to the country’s economy between 2016 and 2018 is visual arts (CEA Creative Economy Review, 2021).

The value of creative goods exports has been decreasing since 2018, and the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated this trend. As a result, in the first half of 2020, exports of creative goods were down to 3.28 billion US dollars, 1.16 billion USD less than an equivalent period in 2019 (CEA Creative Economy Review, 2021).

In 2017, 826,026 individuals were classified as creative workers in Thailand, representing around 1.5 per cent of the total labour force. Of the total, 300,829 or 36 per cent are in the craft industry. The creative workforce has been shrinking since 2016, particularly in the Thai crafts and design sectors. This is due to a decrease in interest among younger generations, changing demand for craft commodities produced for global markets, and increasing costs of production compared to other countries in the world market (CEA Creative Economy Review, 2021; Chudasri, Walker, and Evans, 2012). The number of craftspeople represented in the surveys may not fully reflect the reality of the craft sector, however. In a paper presented at the 18th International Conference on Cultural Economics, Simon Ellis (2014) asserts that due to the nature of craft production, the creativity of local artisans in rural communities is often overlooked in models derived from Europe and other fully-developed economies that focus on employment or entrepreneurship (when these artisans fit the definition of an entrepreneur).

The decline of the creative industries’ contribution to Thailand’s economy is caused by a combination of these factors:

i. Political instability and discontinuity in policy implementation: While creative economy and creative industriesrelated policies have been discussed since 2009, military coups and ongoing political turmoil have prevented effective implementation. Both the 20-year National Strategy and the 12th National Economic and Social Development Plan currently in effect emphasise the digital economy rather than the creative economy, which was the focus of 11th Plan, disrupting policy implementation. The establishment of the CEA in 2018 led to concrete outcomes, generating public-private partnerships in support of the creative economy in Thailand in recent years. The political climate is still unpredictable, however, and any shift in the government’s strategy could affect the continuity of ongoing funding and projects.

ii. The lack of understanding of the cultural and the creative industries: In Thailand, culture is commonly thought of as being connected to national identity and tradition, collectively seen as “the past.” Creativity, on the other hand, is associated with new ideas that can drive society into the future. High-ranking officials view culture as something to be preserved and protected, not needing “creativity”. This could be why the creative industries group title “cultural heritage” adopted from UNCTAD’s classification was later changed to “creative originals.”

Cultural tourism, however, is still present in the latest classification. But this is problematic. Cultural tourism refers to “travel concerned with experiencing cultural environments, including landscapes, the visual and performing arts, and special (local) lifestyles, values, traditions, events as well as other ways of creative and inter-cultural exchange processes” (UNESCO, 2004). Based on this definition, all types of tourism present in Thailand can be regarded as cultural tourism. It is important to point out that cultural tourism and Thai food account for 46 per cent of the creative industries (in 2018) even though they are both considered “related industries.” Therefore, including their economic value in the analysis can give a false impression of the economic contribution of the creative industries to Thailand’s GDP. A recent study by UNESCO shows that the contribution of cultural and creative industry sectors to national GDP in Thailand cannot be accurately measured due to a lack of reliable data (UNESCO, 2021).

iii. New media and the changing digital landscape: The revolution in digital technology is changing the way Thai people live. It was reported that over 75 per cent of Thailand’s population use the internet, 16 per cent more than the global average. Thais’ average daily internet usage is nine hours, ranking fifth globally; the world average is six hours and 43 minutes (Nation, 2020). This phenomenon has opened up more opportunities for the creative industries, especially in the software industry. The coronavirus pandemic has accelerated the adoption of digital platforms and ways of working, but not all industries have seen the benefits of the increased reach. The entertainment industry, for example, has been forced to find alternative income streams and production has been heavily impacted. Independent studios and smaller productions have found paths to distribution via new or established streaming services in place of full-scale theatre releases. With any disruption of this magnitude, there are opportunities, but also risks and challenges; creative workers and organisations in the fields of performing arts, film, and broadcasting must adapt to the changing landscape (Ramasoota and Kitikamdhorn, 2021).

Paths Forward

To encourage creative industries to grow, strengthen Thailand’s creative economy, and achieve sustainable development in the long term, steps must be taken to address the challenges.

First, we need to strengthen long-term strategy and provide consistent funding opportunities for creative workers and organisations. The decline of the creative industries’ contribution to Thailand’s GDP correlates with the focus shift from the creative economy to the digital economy. The digital economy is favoured for the belief that it could lead to more concrete products and services in the short term. It is crucial to remember that the creative economy may take longer to implement and see visible results, but its impacts extend beyond the creative industries and their economic value. The creative economy, once it reaches its maturity, will keep cultural significance alive. It will connect people of diverse backgrounds and brings about unity in society.

Moreover, the creative economy is closely related to the digital economy as well. Innovative technology can enhance and add value to the creative industries, and the digital industries can greatly benefit from the creativity embedded in culture and tradition. Only when the creative economy’s potential is fully recognised in government strategy and policies, and funding is provided for the creative industries to improve the processes of cultural and creative productions will we begin to see its sustainable economic and social impacts.

Second, we must develop reliable methods of measuring the true contribution of the creative industries to GDP. Because the creative economy is based on creativity, culture, and knowledge, it is unique to each location. The classifications and models provided by international organisations like UNCTAD need to be adapted to fit the conditions of Thailand. As mentioned earlier, the method of data collection and the criteria used to determine the contributions that are derived from other developed countries are not necessarily suitable for Thailand. In addition, there has to be agreement on what activities should be included in the creative industries. We cannot deny the immense contribution of cultural tourism to Thailand’s economy, but it is difficult to classify tourism in Thailand as “cultural” or not. The same thinking can be applied to Thai food and traditional medicine, which are considered related industries. Related industries have always been included in national statistics, skewing the contribution of the creative economy to appear much larger in scale than if they were excluded. In order for creative industries to be adequately developed and to reach their potential, this distinction is important. An understanding of their real contribution needs to be reached to make the right strategic decisions and offer the right support.

Third, we must facilitate the development of skills to allow artists and creative/ culture workers to keep up with the global advancement of technology. Even with the high growth rate of the software industry in recent years, there is still a lack of specialists and skilled labour available (DEPA, 2021). Without the knowledge and tools necessary, creative workers cannot keep up with digital disruption and transformation. Just as the nature of the creative economy is different in each country, skill-development programmes should be contextual and in consonance with the existing environment. Collaboration is key to creativity and learning; thus, knowledge and experience sharing is encouraged. For the creative economy to be sustainable, a creative education needs to be implemented nationwide. This will allow children to express their creativity and develop their creative potential to benefit society at large.

Finally, we must strengthen local governance and community participation in the creative industries programmes. Jane Jacobs (1961, 238), an American social activist and urban planning pioneer, observes “cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” The long-standing success of the Creative Chiangmai Initiative can be attributed to its development committee that consists of a wide range of stakeholders, including those from education, government agencies, companies, and local communities (Creative Chiangmai, 2020). The development of the creative economy cannot be sustainable if it is led by government policy alone. Everyone’s opinion in each community has to be heard and considered. All of the projects implemented should welcome people from all sectors and all generations to participate and benefit from. It is only when everyone feels included that a creative economy can grow organically.