The ASEAN region has made progress in many sectors, but challenges remain, especially in the area of girls’ and women’s access to health and education.

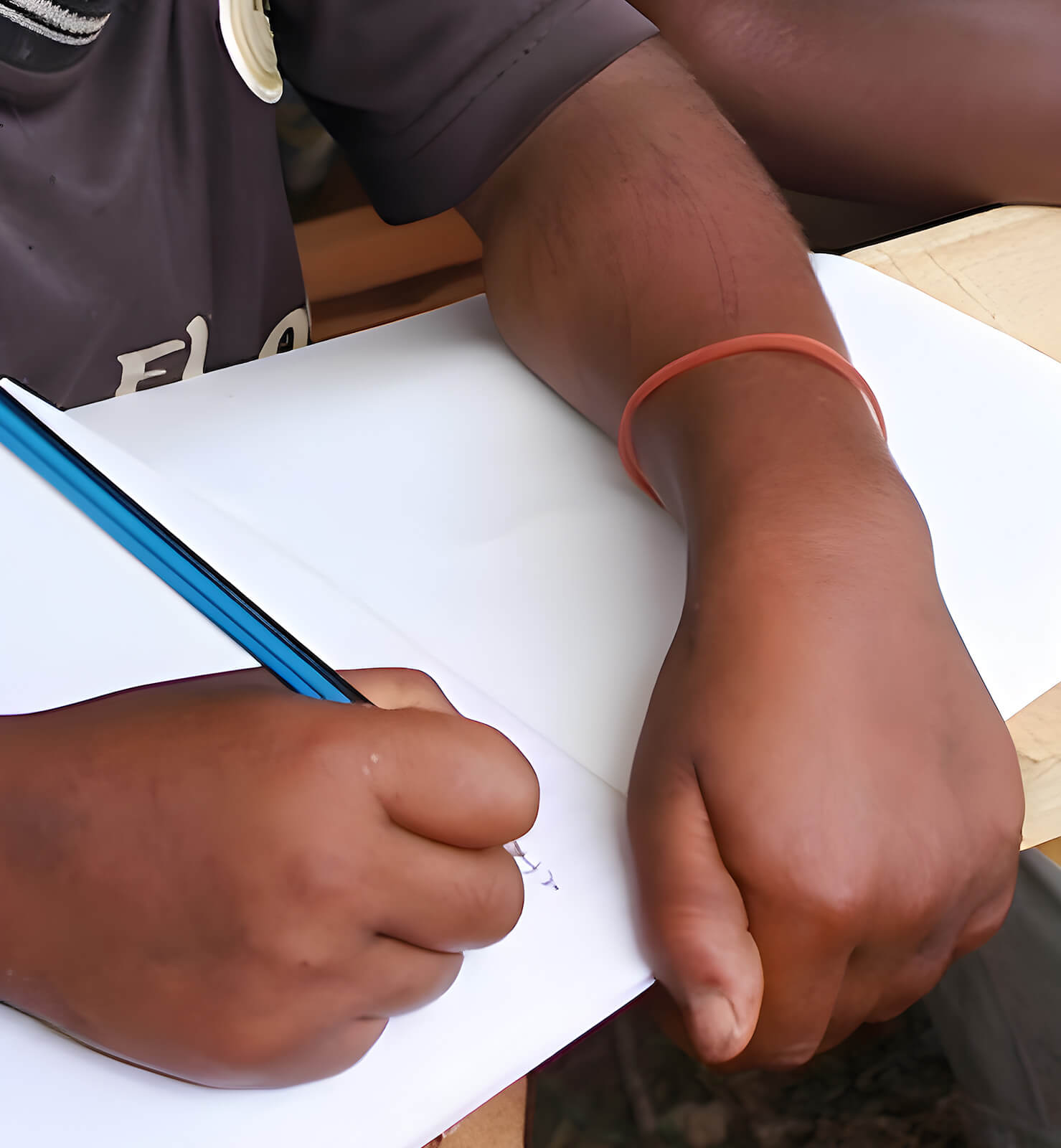

Meryana (not her real name) is a 12-year old girl from Noinbila, a small village in South Central Timor Regency, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. This year, she had to give up on her dream of going to junior high school. Due to economic hardships exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, her parents could only send one of their children to school, Meryana’s older brother, Ronald (not his real name).

East Nusa Tenggara’s harsh geographic conditions have forced many families, like Meryana’s, to seek other sources of income. Most people in the area rely on natural resources for their livelihood, like farming. However, some villages in South Central Timor Regency often experience water shortages due to the long dry season, which then limits the harvest period to just once a year. Villagers would store their crops for the following year’s stock or until the next harvest season. Agricultural production would only be sufficient for household consumption.

To survive these harsh conditions, Meryana is expected to augment her family income by doing domestic work, such as fetching clean water up the hills or helping her parents in the corn fields. Like most girls from her village, she is also expected to take on jobs like waitressing in Kupang, the capital of East Nusa Tenggara Province.

Meryana’s case shows that the burden of the pandemic is bearing down more heavily on vulnerable groups, including women and girls in East Nusa Tenggara. In addition, the pandemic has made long-existing economic and social inequities more evident.

The gender barriers in education experienced by Meryana are also evident in some ASEAN countries. Studies indicate that girls are more likely to drop out of school early or miss school days than boys. In many cases, girls are forced to stay at home and perform household chores instead of attending school. Moreover, some communities believe investing in boys’ education is more worthwhile than investing in girls’, as they see boys as the future breadwinners or community leaders. These barriers deny girls’ right to education, and also limit their opportunities for economic empowerment and personal development. This cultural bias against girls’ education is particularly evident in rural areas, where girls are more likely to be excluded from school.

Another issue is the lack of access to educational resources. In many ASEAN countries, some schools are located far away from students’ homes, and transportation is not readily available. This lack of access can disproportionately affect girls, who may face safety concerns and cultural barriers to travelling and attending school.

It has therefore become imperative to develop and implement policies and programmes at the regional level that ensure equal access to education for all regardless of gender. These include investing in girls’ education and supporting programmes that address the root causes of gender inequality, such as early marriage and discrimination. The ASEAN Committee on Women (ACW), in partnership with the ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Education (SOM-ED), will develop and implement guidelines on the elimination of gender stereotypes and prejudices in the education system by next year. In addition, the private sector can also play a role by investing in education and training programmes that target girls and women, providing them with the skills and knowledge they need to succeed in the workforce.

In addition to education, gender barriers that affect women’s access to healthcare is still apparent in the region. Women in rural and remote areas often face limited access to healthcare facilities and services due to geographic, economic, and cultural obstacles. They also face discrimination from healthcare providers who may not take their health concerns seriously or who may hold negative attitudes towards women’s reproductive health.

Moreover, cultural beliefs and practices around reproductive health also impact girls’ and women’s access to healthcare and education. Access to reproductive healthcare, including maternal and family planning services, is often limited due to cultural and religious beliefs, which could lead to unintended pregnancies and maternal mortality.

To address these challenges, investment in health infrastructure and services that are accessible and responsive to the needs of women and girls, is necessary. This includes allocating resources to expand access to family planning and maternal healthcare services, and address the social and cultural norms that limit women’s access to healthcare. Women’s groups and civil society organisations can also play a critical role in advocating for women’s rights and raising awareness about the importance of gender equality in healthcare.

Ultimately, eliminating gender barriers to education and healthcare requires a holistic approach that starts with addressing the root causes of gender inequality. These include breaking down the social norms and stereotypes that perpetuate gender-based discrimination, and investing in policies and programmes that promote gender equality and empower girls and women.

While gender barriers in education and health remain significant challenges in the region, it is important to acknowledge ASEAN’s notable progress towards achieving gender equality and promoting inclusive development. One of the key initiatives undertaken by ASEAN in this regard is the adoption of the ASEAN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women and Children. It includes provisions for education and awareness-raising programmes to prevent violence and access for healthcare and social services for victims. In addition, the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community Blueprint signifies ASEAN’s commitment to promote gender equality and empower women and girls in the ASEAN region. It includes targets for increasing women’s access to education and healthcare, and measures to prevent and respond to gender-based violence.

The development of quality gender data and robust evidence is critical to informed decision-making. It will ensure that policy responses are effective and responsive to the needs of women and girls in the region’s most vulnerable and marginalised groups.

Breaking barriers to health and education will allow many girls like Meryana to pursue their dreams. “I want to be a teacher, a role model for children in Noibila [Village] to look up to. There are not many teachers here in this village. To become a teacher, I have to continue my studies, at least until senior high school. If my parents allow me to work in Kupang, I will use my savings to cover the tuition fees. I will be teaching in Noinbila. I want to inspire children in my village. I want them to be brave, and dream big.”

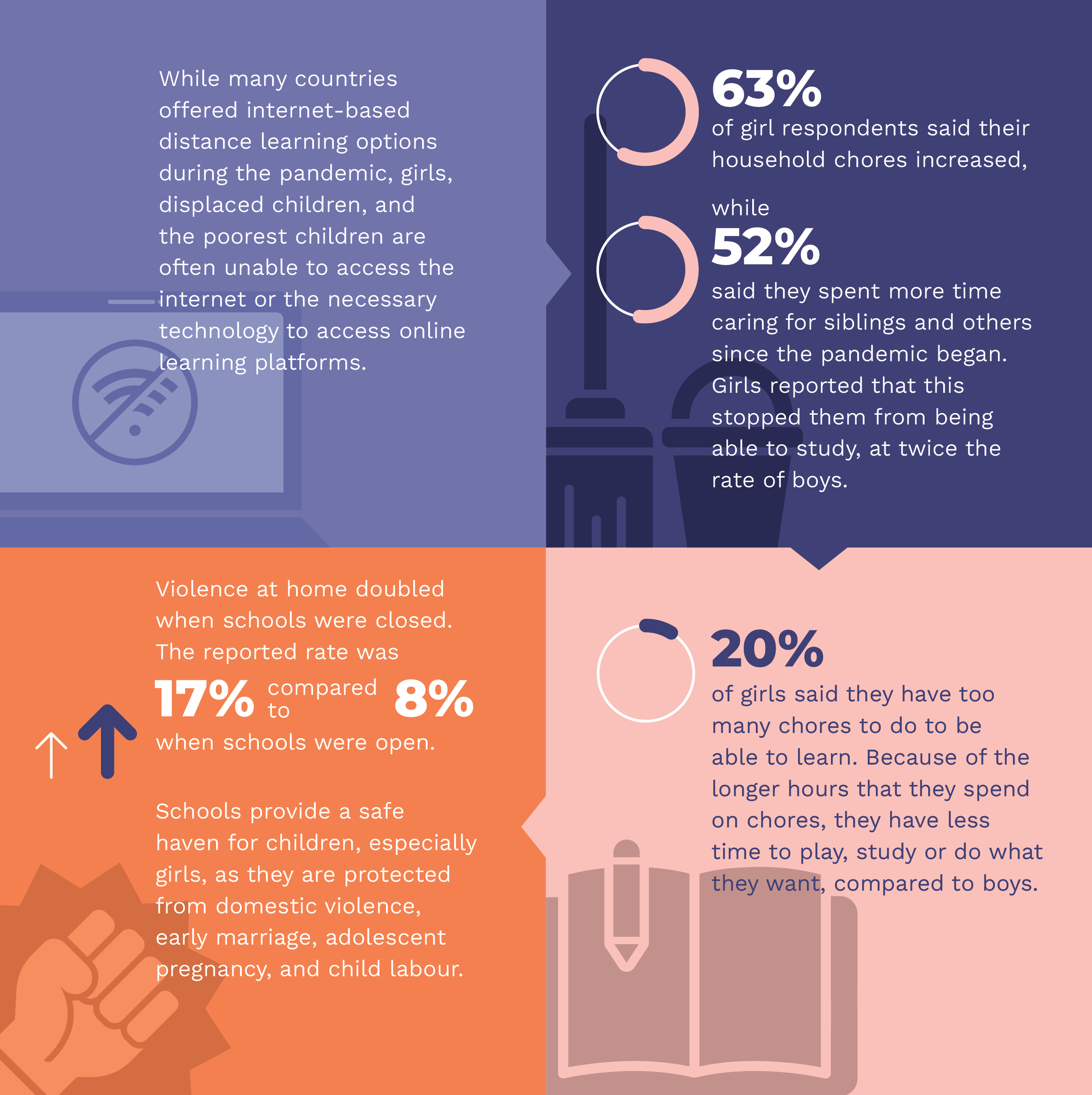

IMPACT OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON GIRLS’ EDUCATION, SAFETY

The global survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children, undertaken by Save the Children, revealed the following: