The COVID-19 pandemic may have restricted mobility for most of us who live in ASEAN's bustling cities, but the reality is we still have to travel within our city's confines using private or public transport. We sleep and wake up to inescapable sounds of vehicles rumbling by. We go about our lives inhaling air pollutants spewed by a constant stream of vehicles plying our streets.

In short, transportation is as much part of urban life as people. Any talk of transforming cities into liveable and sustainable spaces must necessarily include transportation in the equation.

In short, transportation is as much part of urban life as people. Any talk of transforming cities into liveable and sustainable spaces must necessarily include transportation in the equation.

Road Congestion Due to Rapid Motorisation, Underdeveloped Infrastructure

Urban transport systems function to support the economy of cities and nations. Efficiently moving people and commodities from their point of origin to their destination translates to lower costs and higher productivity.

The dispersal of commercial, residential, and recreational spaces over a large expanse of land means more people are commuting at longer distances to reach jobs, markets, and services. However, in many cases, a city’s mass public transport system, such as buses and light rails, has limited coverage area or passenger load, or provide unreliable service to meet public demand. This increases urban commuters’ dependence on personal or privately owned motorised transport (further boosted by other factors such as rising household incomes in the region). The increasing volume of sales of passenger vehicles and motorcycles in ASEAN Member States prior to the COVID-19 pandemic is one indicator of this growing dependency.

Those without personal vehicles rely on the “inner city paratransit systems” that provide “personalised, flexible, and affordable public transport service” (UNESCAP Committee on Transport, 2018). They include minivans, angkot (Indonesia), songthaew (Thailand), tuktuk (Thailand), jeepney (Philippines), and tricycle (Philippines), all of which only add to the volume of vehicular traffic.

Meantime, the carrying capacity of existing road networks is often inadequate. Because of the massive investment required, expansion of road infrastructure is slow and constantly outpaced by the rate of increase in motor vehicles. Adding to the problem is the ineffective traffic management system in many cities.

These elements serve up the perfect storm for daily gridlocks, especially at peak hours, resulting in loss of time and money.

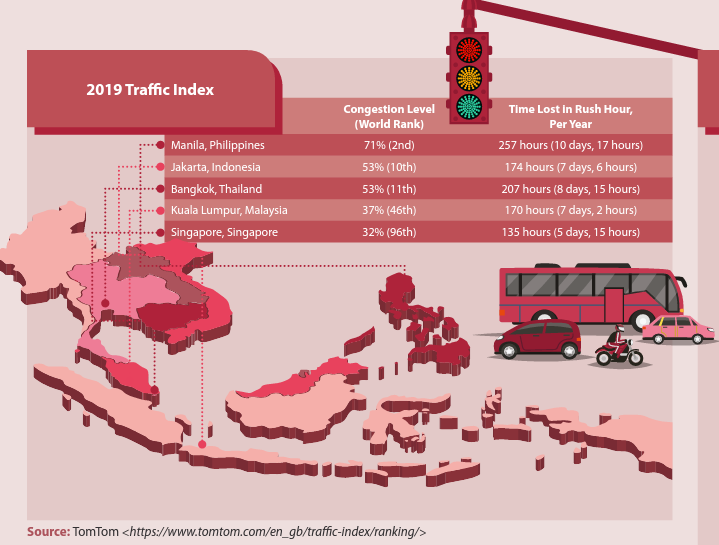

Before the pandemic ground cities to a halt in 2020, the TomTom Traffic Index, which tracks traffic conditions in over 400 cities around the world, recorded Manila’s congestion level in 2019 at 71 per cent. This means that a 30-minute trip during rush hour took 71 per cent extra time to complete. In total, drivers spent 10 days and 17 hours stuck in traffic in 2019, making Manila the second most congested city in the world and the top in Southeast Asia. Jakarta and Bangkok occupied the 10th and 11th spot, respectively, both with congestion levels of 53 per cent during the same year.

A 2018 study by the Japan International Cooperation Agency estimates that Metro Manila loses 3.5 billion pesos per day, or 70 million US dollars in today’s exchange rate, due to heavy traffic. Indonesia’s Ministry of National Development Planning, meanwhile, values the economic cost of congestion in Greater Jakarta at about 65 trillion Indonesian rupiah per year, or 4.48 billion US dollars in today’s exchange rate, based on an OECD report.

Longer travel time also takes a toll on the well-being of commuters. It cuts into family, socialisation, and rest hours, and adds to mental and physical stress.

Traffic Accidents

Modern streets and buildings are designed primarily for motor vehicles, particularly cars, trucks, and buses. In recent years, Southeast Asian cities have accommodated the growing number of motorcycle riders and cyclists by designating special motorcycle, scooter, or bike lanes or window hours along major roads. In contrast, walkways are often nonexistent or if present, they are narrow, not interconnected, and occupied by vendors, parked cars, and other obstructions. This has forced pedestrians and a wide range of vehicles to “share” road space—a recipe for disaster. It exposes pedestrians, especially older people, people with disabilities, and children, to unnecessary risks.

Road fatalities in the region are particularly high. The Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018 of the World Health Organization shows that its Southeast Asia cluster logs 20.7 road traffic deaths per 100,000 population, higher than the global rate of 18.2 deaths per 100,000 population. WHO’s Western Pacific cluster, meanwhile, has a road fatality rate of 16.9 deaths per 100,000 population. In both clusters, riders of motorised two- and three- wheelers comprise most of the casualties.

The weak enforcement of traffic regulations, such as wearing of seatbelts and motorcycle helmets, and poor road accident emergency response also keep urban streets in Southeast Asia from being safe zones.

Poor Air Quality from Vehicle Emissions

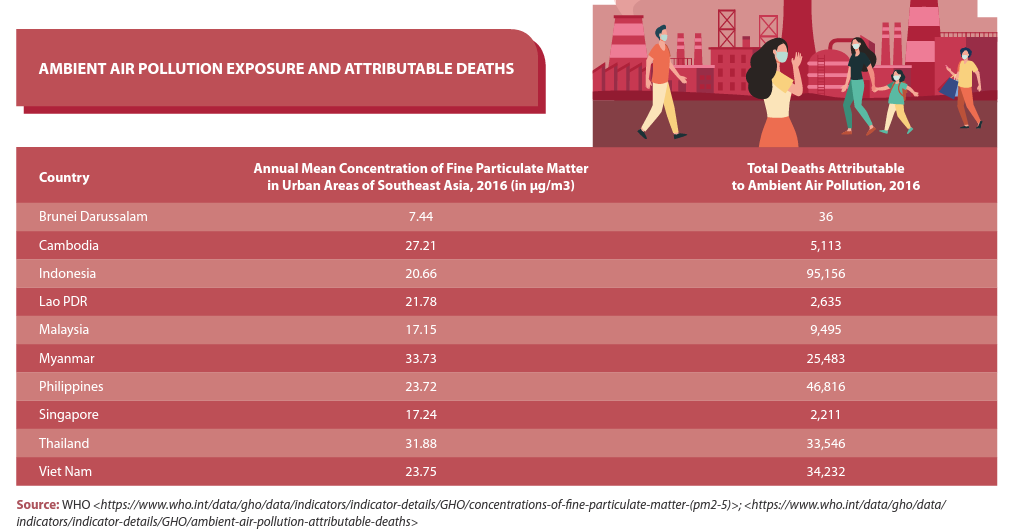

Motor vehicles are among the main sources of air pollution in cities. They emit fine particulate matter—defined as inhalable particles that measure 2.5 microns or less in diameter—and noxious chemicals such as lead, ozone, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and carbon monoxide. With more vehicles on the road moving at snail pace during peak hours, more of these pollutants are released into the atmosphere, degrading ambient or outdoor air quality.

These transport-related pollutants present serious health hazards and could lead to premature death. Fine particulate matter, also referred to as PM2.5, is known to aggravate symptoms of asthma and emphysema and increases one’s risk of developing heart disease and lung cancer, according to WHO (2018). Ground-level ozone and nitrogen dioxide, meanwhile, could reduce lung function and cause a variety of respiratory illnesses.

Data from WHO show that Southeast Asian cities have among the highest levels of PM2.5, most exceeding WHO’s annual mean concentration threshold of 10 micrograms per cubic meter of air (μg/m3). Some Southeast Asian countries also reported an alarming number of deaths from lower respiratory infections; trachea, bronchus, and lung cancers; ischemic heart disease; stroke; and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, all traceable to ambient air pollution.

Improving the Mass Public Transportation System of Cities

One of the fail-safe strategies being pursued by Southeast Asian governments to address their transport and mobility problems is the improvement of their urban centers’ public transportation system by expanding service routes, creating interconnection between various modes, and applying new technologies to boost speed and efficiency. Authorities and experts believe that this will incentivise urban commuters to use public transport instead of their personal vehicles, which in turn is expected to simultaneously ease road congestion and reduce harmful emissions.

Over the past few years, a flurry of public transport projects has been initiated in Southeast Asian cities. Viet Nam is completing Hanoi Metro, the first city-wide rail transit system in Hanoi which will consist of eight lines with a combined length of 318 kilometres. The Philippines is extending two of its existing rail lines, LRT Line 1 South Extension and LRT Line 2 West Extension, and adding a new rail route, Metro Rail Transit Line 7, to cover more areas within Metro Manila and reach nearby suburbs.

Indonesia, in addition to completing the first line of Jakarta MRT in 2019, focused on interconnecting its bus rapid transit system (TransJakarta) terminals with those of its MRT, LRT, and regular buses, as well as implementing an integrated ticketing and payment scheme across all public transport modes. These initiatives, which increased service coverage and facilitated transfers, earned Jakarta the 2021 Sustainable Transport Award from an international panel of judges that included the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), Asian Development Bank, World Bank, International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, and Clean Air Asia, to name a few.

The individual countries’ focus on public transport is consistent with the strategic direction of ASEAN. The ASEAN Transport Strategic Plan 2016-2025 cites “intensified regional cooperation in the development of sustainable transportrelated policies and strategies” as one of its major goals, with “promoting the use of public transport in ASEAN cities” as a priority action. The ASEAN Sustainable Urbanisation Strategy includes an urbanisation framework that encourages countries to develop a bus rapid transit system which is deemed quicker and less expensive to implement and more environment-friendly than other transport modes.

Clean Transport Initiatives

Southeast Asian countries have stepped up efforts to reduce air pollution from motorised vehicles. National and city governments alike are encouraging their citizens to take up cycling as a greener and healthier mode of transport within the city. ITDP (2021) reports that in 2019, the city government of Jakarta established some 63 kilometres of safe bicycle trail, which it plans to expand to 500 kilometres this year. Additionally, a programme that lends bikes to commuters free of charge has been launched and is available in 72 stations located near transit hubs.

Initiatives to transition to more environment- friendly vehicles are also underway. The Philippines is implementing a Public Utility Vehicle Modernization Program, which aims to phase out 180,000 jeepney units and replace them with either electric vehicles or Euro-4-compliant (low carbon emission) vehicles. Viet Nam is manufacturing its first electric buses for deployment to five major cities, namely, Hanoi, Haiphong, Danang, Ho Chi Minh, and Cantho. Thailand recently launched a national plan that will see the local production and circulation of one million electric vehicles— including 400,000 cars and pick-up trucks, 620,000 motorcycles and 31,000 buses and trucks—by 2025.

Initiatives to transition to more environment- friendly vehicles are also underway. The Philippines is implementing a Public Utility Vehicle Modernization Program, which aims to phase out 180,000 jeepney units and replace them with either electric vehicles or Euro-4-compliant (low carbon emission) vehicles. Viet Nam is manufacturing its first electric buses for deployment to five major cities, namely, Hanoi, Haiphong, Danang, Ho Chi Minh, and Cantho. Thailand recently launched a national plan that will see the local production and circulation of one million electric vehicles— including 400,000 cars and pick-up trucks, 620,000 motorcycles and 31,000 buses and trucks—by 2025.

Viet Nam, Thailand, and Singapore have also made it compulsory for car manufacturers and importers to put CO2 emission and fuel economy labels (i.e. litres of fuel and/or kilowatt hours consumed per 100 kilometres) on new passenger light-duty vehicles, such as sedans, vans, and pick-up trucks, to make it easier for buyers to shift to cleaner and more efficient vehicles.

This is consistent with the goals identified in the ASEAN Fuel Economy Roadmap for the Transport Sector 2018-2025: With Focus on Light-Duty Vehicles, which include, among others, a 26 per cent reduction in the average fuel consumed per 100 kilometres of new light-duty vehicles; alignment of fuel economy label information across the region; and adoption of national fuel consumption standards for light-duty vehicles in all markets.

Safer Roads for All

Southeast Asian countries enacted new traffic policies to make roads safer for motorists, passengers, and pedestrians. Cambodia amended its traffic law in 2020 imposing stiffer fines and penalties for traffic violations, such as drunk-driving, non-wearing of helmets, and overloading of passengers. Starting January 2020, Malaysia began enforcing its child restraint policy covering all private vehicles. The Philippines is poised to implement a similar child car seat regulation which it passed two years earlier.

To further bring down traffic-related injuries and fatalities, the ASEAN Member States are pursuing other road safety initiatives, guided by the strategies outlined in the ASEAN Regional Road Safety Strategy. These include strengthening road safety management; designing road and roadside safety initiatives that fit local contexts and available resources; promoting the use of safer vehicles; ensuring compliance of road users with traffic regulations; and instituting speedy and competent post-crash response.

New Developments

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing the discourse surrounding road transport and mobility. Telecommuting or telework— which has become a stopgap measure during the pandemic lockdowns—may now become a permanent alternative work arrangement for some occupations even after the pandemic is over. To what extent this will reduce (if at all) road traffic remains to be seen. Telework is also opening the possibility of workers opting to live outside urban centres and creating a reverse migration trend.

At the other end of the spectrum, paranoia over close physical contact, especially with the emergence of more contagious COVID-19 variants, may push people to shun the use of public transport. The 2021 Deloitte Global Automotive Consumer Study, in fact, indicates this trend, with 52 per cent of Southeast Asian consumers now preferring to use personal vehicles compared to only 37 per cent before the pandemic. With the continued threat of COVID-19 and fear of similar outbreaks hovering for years to come, governments will need to study and institute long-term health and safety standards for mass transit systems, including smart solutions (e.g. electronic ticketing, contact-tracing apps, crowd-management solutions), to (re)gain the trust of commuters and make the operation of public transit systems viable.

References:

ADB, ACGF and SEC. (2020). Green Infrastructure Investment Opportunities: Philippines 2020 Report. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/653566/ green-infrastructure-investment-philippines-2020.pdf; Dara, V. (20 March 2020). Traffic Law Changes in Force. Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved from https://www.phnompenhpost.com/ national/traffic-law-changes-force; Deloitte. (2021). Global Automotive Consumer Study: Southeast Asia Perspectives. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/sg/en/pages/consumerbusiness/articles/global-auto-consumer-study-sea.html; European Climate Foundation. (2019). Green Infrastructure Investment Opportunities: Viet Nam 2019 Report. Retrieved from https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/final_english_giio_vietnam_report.pdf; ITDP. (6 May 2021). Jakarta Is What Resiliency Looks Like. Retrieved from https://www.itdp. org/2021/05/06/jakarta-is-what-resiliency-looks-like/; ITDP. (2021). Sustainable Transport Award Winner 2021: Jakarta, Indonesia. Retrieved from https://staward.org/winners/2021jakarta-indonesia/; JICA. (20 September 2018). JICA to Help Philippines Ease Traffic Congestion in Metro Manila. Retrieved from https://www.jica.go.jp/philippine/english/office/topics/ news/180920.html; OECD. (March 2021). OECD Economic Surveys: Indonesia. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/economy/surveys/indonesia-2021-OECD-economic-survey-overview. pdf; Theparat, C. (25 March 2021). Govt. Ups E-car Drive. Bangkok Post. Retrieved from https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/2089087/govt-ups-e-car-drive; WHO. (2 May 2018). Ambient (outdoor) Air Pollution. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health; WHO. (2018). Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/277370/WHO-NMH-NVI-18.20-eng.pdf?ua=1; UNESCAP Committee on Transport. (2018). Assessment of Urban Transport Systems and Services. Retrieved from https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/6E_Assessment%20of%20urban%20transport%20systems%20and%20services_0.pdf