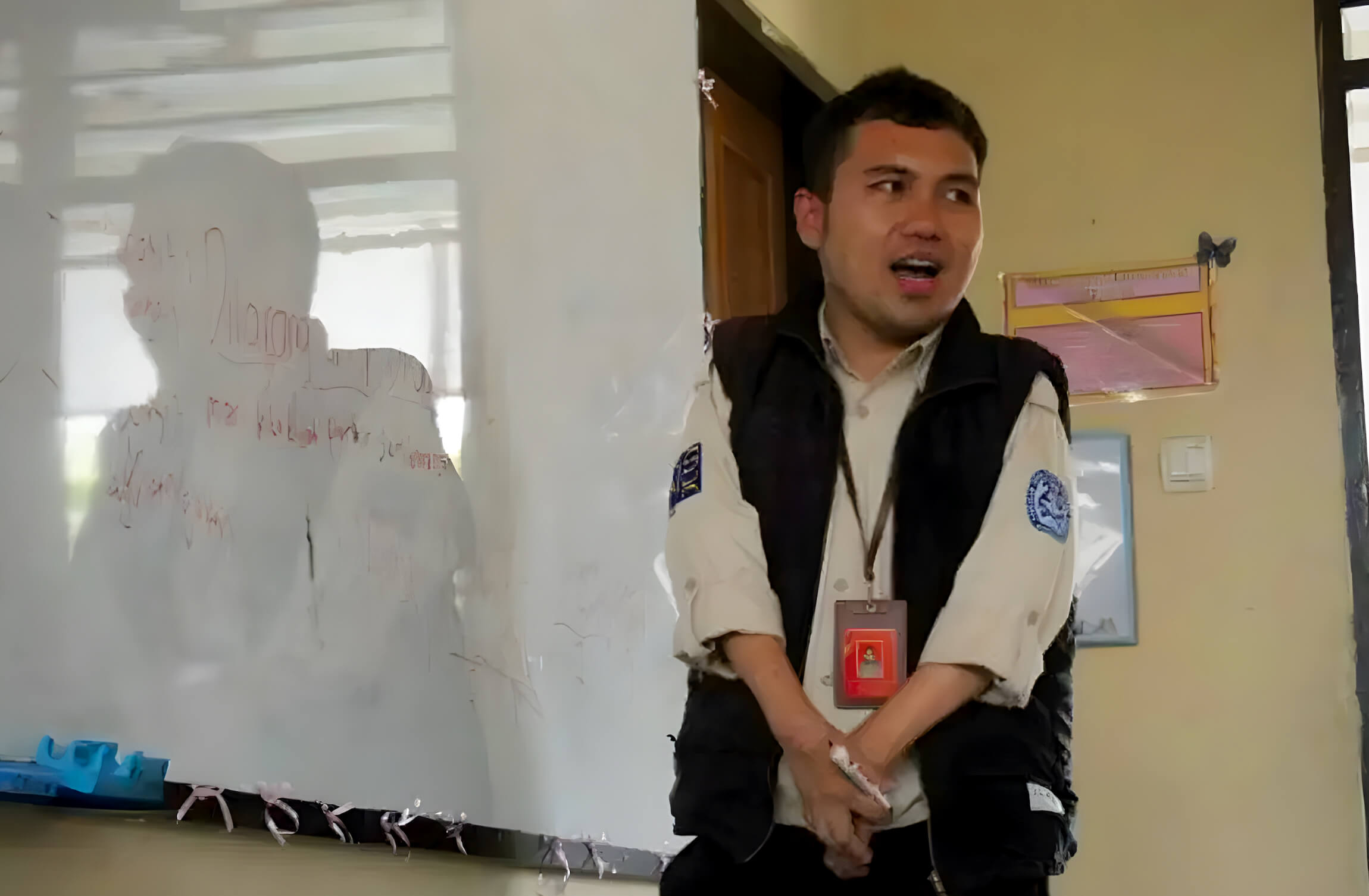

Every day, Jenilyn de la Cruz gets up at 3:30 a.m. to make her 7:30 a.m. class at the Lopero Elementary School, in a remote village in Zamboanga del Norte, Southern Philippines. It is a gruelling 65-kilometre motorcycle ride to the school, one of over 7,000 multigrade schools in the country. Teacher Jen is one of only four full-time teachers handling multigrade classes and multiple subjects in the school. She handles a combined class of 5th and 6th graders, and teaches all eight subjects required in the national curriculum.

The multigrade system is not a new concept. Early schools placed pupils of different ages in one classroom under the guidance of one teacher. It was only sometime in the mid-19th century that single or monograde classes were introduced, with students in the same age range grouped into one class and subject to the same curriculum.

Although the monograde structure is now the standard worldwide, multigrade schools or classes still persist in Southeast Asia. A 2012 study by the Southeast Asia Ministers of Education Organization Regional Center for Educational Innovation (SEAMEO INNOTECH) noted that eight ASEAN Member States operate multigrade education programmes as part of their national education policy.

Multigrade education programmes are commonly implemented in rural or sparsely populated areas. They are set up when regular schools are too costly to build and maintain, and when teachers are scarce. ASEAN governments deem the multigrade system an effective strategy for delivering education services to children from the farthest and most inaccessible communities.

Multigrade education: Some approaches

Countries have different approaches to multigrade education. In a 2018 study of multigrade teaching practices in Thailand, Buaraphan et al. found that some schools offer all multigrade classes from Kindergarten to sixth grade, in two-grade or three-grade combinations. However, some schools have a “hybrid” arrangement that includes both blended and single-grade classes.

Buaraphan et al. observed that teachers typically began by introducing the topic to the whole class, then divided the students by grade to work on specific tasks, and later, reassembled them to wrap up the lesson. The approach gave older students an opportunity to interact with and assist the younger ones.

In terms of outcomes, multigrade teaching was effective in enhancing Thai students’ reading and writing skills and their ordinary national education test (O-Net) scores. This was attributed to the smaller number of students,which allowed teachers to have more time to attend to their students’ learning needs.

In the Philippines, meanwhile, the hybrid or mixed multi- and single-grade set-up is more common based on a 2021 study done by the Department of Education (DepEd) and SEAMEO INNOTECH. Grades I and II, Grades III and IV, and Grades V and VI are the most frequently combined grades. The average teacher-pupil ratio is 1:19.

Multigrade teachers follow the national curriculum for each grade, but their teaching strategies vary. Some implement the quasi-monograde method of alternating between different grades, i.e., instructing students in one grade while another grade works on individual or group activities. Other teachers gather all students to discuss the topic before dividing them into groups for grade-appropriate tasks or activities.

The DepEd-SEAMEO INNOTECH study found that multigrade students outperformed monograde students in some areas of the Philippines’ national achievement test (i.e., Math and Social Studies). They also demonstrated better social skills and higher self-esteem. However, high repetition and dropout rates remain a problem in multigrade classes.

Prospects and challenges

Education officials recognise the promise of multigrade education to contribute to universal and inclusive basic education. However, the quality of multigrade education programmes in the region is difficult to determine because of insufficient up-to-date data. Experts recommend enhancing monitoring and evaluation to optimise the potential of multigrade education initiatives. How do teachers adapt the curriculum and manage different grade levels? What strategies are effective in improving learning outcomes? Do multigrade learners measure up to expected levels of competency? What factors contribute to student attendance, engagement, and completion? These are just some of the data that need to be collected to understand current challenges. They will help decision-makers design better training for multigrade teachers, tailor curricula and learning materials for multigrade classes, and allocate resources to where they are most needed and create the greatest impact.

Additional information on multigrade was provided by the Educational Innovation Unit of SEAMEO INNOTECH.