I first visited Aceh in early 2005 while working at the United Nations (UN) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in Kobe. I was shocked by the sight of the entire landscape, buildings, and houses swept away by the tsunami. It was even more heartbreaking to witness the traces of people’s lives, knowing that they were gone and that their lives had been lost. A few months later, I was posted to Aceh to work with the UN Office for the Recovery Coordinator for Aceh and Nias (UNORC). After another earthquake struck Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in June 2006, I was transferred there to assist with response and recovery coordination.

During my two years of service in Indonesia, particularly in Aceh, I became acutely aware of the critical importance of leadership, education, and effective international assistance. In principle, disaster response and recovery cannot proceed without government leadership. In a major disaster, the national government assumes leadership, while local authorities are responsible for managing regular hazards. Though crucial, international assistance does not replace government leadership but serves as a support system that enhances government response and recovery efforts.

At the time of the Indian Ocean Tsunami, the Aceh-Nias Reconstruction and Rehabilitation Agency (BRR), an Indonesian government agency, played a major role in coordinating and implementing the recovery program. Later, the National Agency for Disaster Countermeasure (BNPB) and the Local Disaster Management Agency were established, both contributing to increased capacity and interest in disaster management. The growth in budget allocation and increased focus on disaster management as a result of these initiatives has been a significant achievement.

Many international organisations and NGOs had never experienced such massive relief and recovery efforts before the tsunami, and they encountered numerous challenges, including a lack of communication, coordination, and information sharing between stakeholders. There was certainly much to learn. The shortage of materials and personnel also posed significant challenges, leading to delays in relief and recovery programs.

Disaster education extends beyond students and children. Everyone should have a basic understanding of what a tsunami is, what disaster preparedness or risk reduction means, and how to respond to emergencies. This knowledge guides us in taking appropriate action and preparing for potential future disasters. Moreover, various institutions such as governments, schools, hospitals, academia, the private sector, and communities must understand their respective roles in risk management. This will lead to building a resilient society.

In 2011, seven years after the Indian Ocean tsunami, the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami struck Japan. My visit to the affected areas reminded me of what I had witnessed in Aceh in 2005. I had never expected to see such similar devastation again, especially in Japan. The experience was tremendously shocking. This disaster is often referred to as a “triple disaster”—an earthquake, a tsunami, and a nuclear accident. One reason for the extensive damage was the delay in evacuating residents from the tsunami. Many people hesitated because they believed the tsunami would not reach them, as previous hazard maps had shown that their area was not within the tsunami inundation zone. In addition, the earthquake caused the disaster radio system to fail, and residents felt reassured when the warning did not sound.

The key lesson from this experience is that systems are not infallible. Whether or not warnings are issued, we must rely on what we have learned to make our own decisions. Furthermore, we should not become overly dependent on past experiences or assumptions.

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident was mainly caused by the loss of cooling function, resulting from the loss of external power due to the earthquake, compounded by the failure of almost all emergency power supplies due to tsunami flooding. Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings (TEPCO) explains the root cause of the accident as follows: “The reinforcement of countermeasures against severe accidents stagnated, as decisions were shaped by past assumptions that the likelihood of a severe accident due to the loss of all power sources was minimal, reducing the perceived need for further safety improvements. Despite insufficient knowledge about tsunamis, it was judged that the possibility of one exceeding expectations was low, and countermeasures were not thoroughly considered. Additionally, on-site accident response training and the provision of materials and equipment were inadequate. As a result, critical plant condition information could not be shared, and rapid, accurate depressurisation operations were not executed.” This resulted from a lack of understanding and an underestimation of the risks, which prevented sufficient preparedness measures from being implemented. This scenario is not unique to Fukushima; many disasters share similar dynamics. The reality is that when a disaster strikes, “one can never do more than they are prepared to do” (Prof. Fumihiko Imamura, IRIDeS, Tohoku University). Different countries and regions face varying risks; thus, it is crucial to use the all-hazards approach to conduct risk assessments. This approach involves not ruling out any possibilities, but considering them all, including natural hazards, environmental and technological threats, and cascading and compound disasters. It is important to remember that science and technology will play a significant role in identifying and communicating risks.

In many cases, even if robust preparedness measures, such as hazard maps and early warning systems, are in place, they may be ineffective if people do not utilise them properly. For instance, if an early warning is issued but no evacuation actions are taken, the issue lies not with the preparedness measures themselves but rather with human behaviour, potentially due to a lack of disaster education or awareness. Infrastructure such as seawalls can be effective in reducing the impact of tsunamis, but cannot always be a perfect solution. Depending on the magnitude of a tsunami, evacuation action is still necessary. In the event of an earthquake, it is essential to equip buildings and houses with earthquake-resistant or seismic isolation structures to protect lives and assets.

Furthermore, no matter how well-prepared we are, the damage caused by disasters cannot be completely eliminated. Severe catastrophes will inevitably result in a certain extent of damage. Therefore, we must also be prepared to provide practical assistance in emergencies. For example, managing evacuation centres becomes highly complex when a large number of evacuees is involved, especially during multiple or compound disasters such as a typhoon during the COVID-19 pandemic or an earthquake amid a heatwave. Moreover, the needs of evacuees, including older adults, infants, children, women, and people with disabilities, vary, making it a significant challenge to provide safe and accommodating spaces for all. This challenge is not solely the responsibility of local governments; everyone must contribute, cooperate, and participate in managing these spaces.

We are witnessing increased frequency and intensity of natural hazards, which may worsen. Addressing future scenarios using current strategies and risk reduction measures will not suffice; scaling up these measures is imperative. Both top–down approaches and local-level initiatives are essential for enhancing risk reduction capacities and reducing vulnerabilities. In Japan, the concepts of “public help,” “mutual help,” and “self-help” are well-known. It is important to increase mutual help and self-help gradually. Japan has been actively promoting the development of district or community disaster preparedness plans to understand residents’ needs and prepare for necessary support during emergencies at the local level.

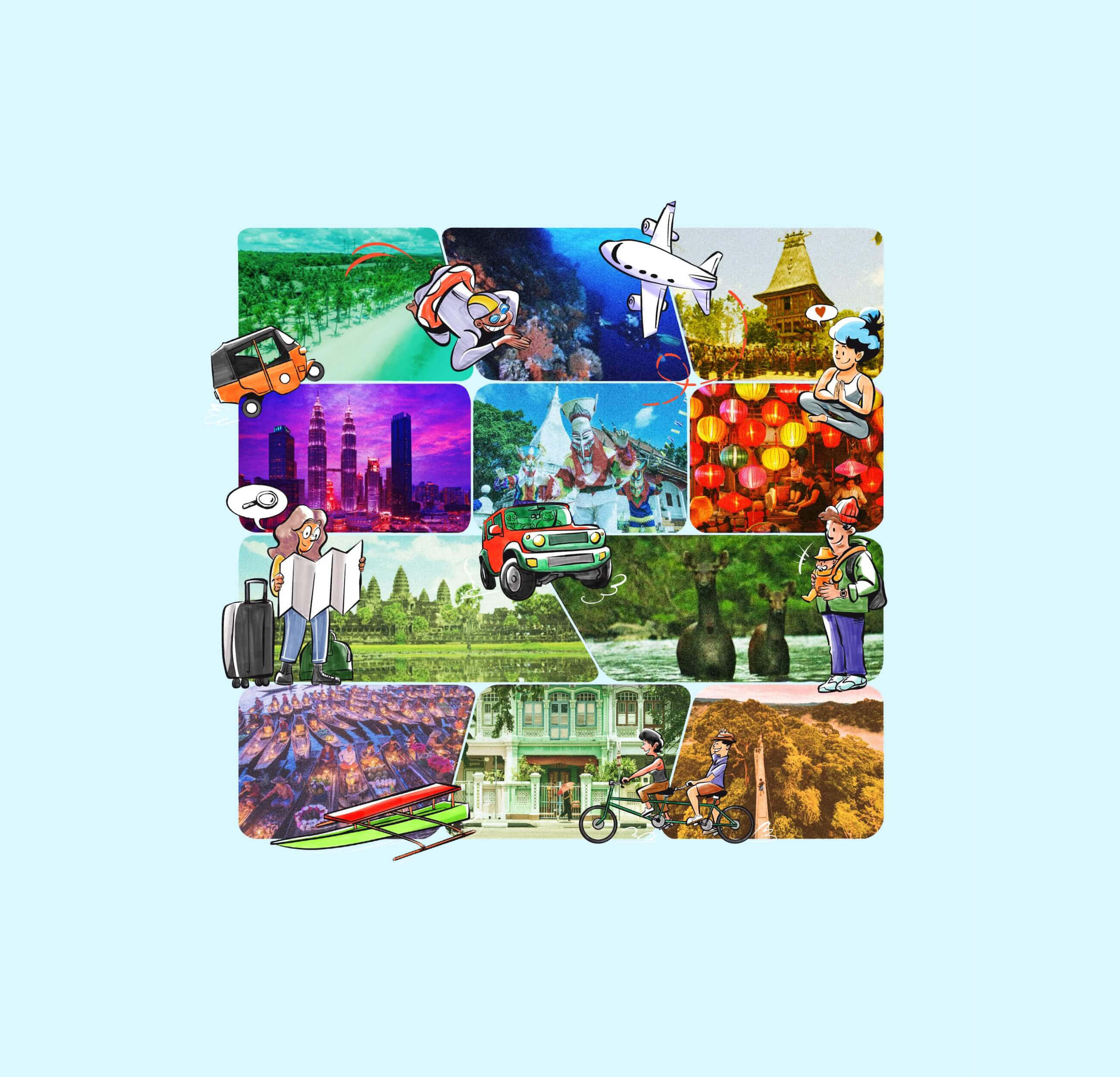

The ASEAN region is particularly disaster-prone. It is essential to share experiences, challenges, and information across countries and tailor support to each nation’s needs and circumstances. Additionally, disasters do not respect national borders, making regional and international collaboration essential when preparing for major disasters, with ASEAN leadership playing a critical role.

Dr. Takako Izumi is a professor of the International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) and Graduate School of International Cultural Studies in Tohoku University, Japan. She also serves as program director of the Multi-Hazards program under the Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU). Her research interests include international strategies for disaster risk reduction (DRR), environmental disaster risk management, and humanitarian assistance.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of ASEAN.