“In education, we cannot afford a simple goal,” Najelaa Shihab told The ASEAN in an interview in Jakarta.

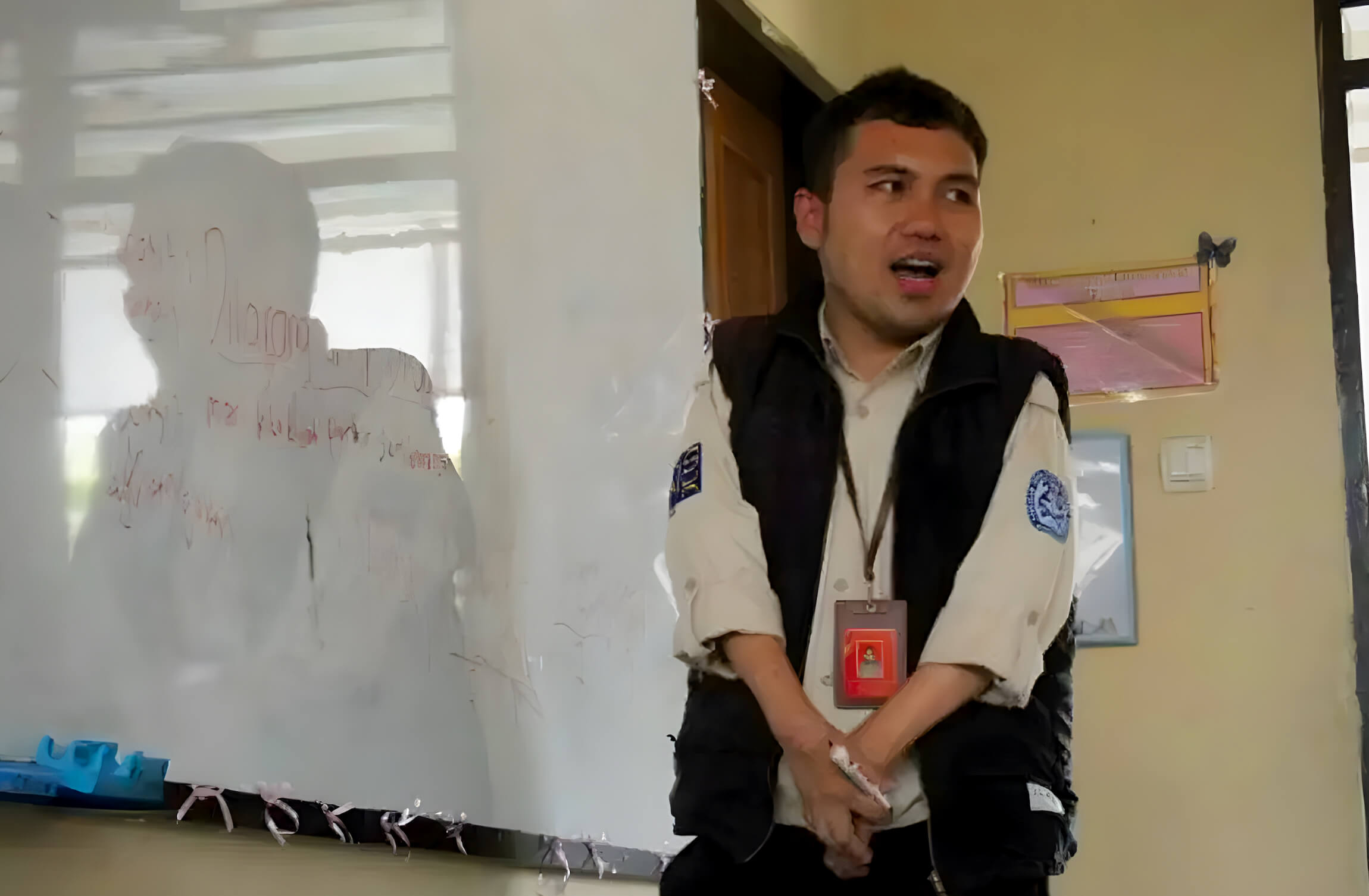

The 47-year-old educator has worked in the field for over two decades. In 1999, she founded her dream school, Cikal, but did not stop there.

Najelaa later established various foundations, such as Yayasan Guru Belajar [Learning Teachers Foundation] and Kampus Pemimpin Merdeka [Independent Leaders’ Campus], to help teachers and school principals, primarily from public schools, improve their skills and teaching methods.

Najelaa’s larger goal was to transform education in her country. In 2016, she launched the social movement Semua Murid Semua Guru [All Students, All Teachers] to celebrate good educational practices and promote stakeholder collaboration. She has worked with thousands of teachers, students, and communities to accelerate access to quality education across Indonesia.

Najelaa reminisced that when she first announced her desire to be a teacher, her family and friends questioned her decision.

“Many people feel that choosing to manage a school or be in the classroom should not be a choice for those who have other options. They said, ‘But you are clever! Why do you want to be a teacher?” Najelaa recalls.

Twenty years later, to her disappointment, this stigma persists.

“There is low interest in becoming a teacher among qualified individuals. The problem isn’t just about the pay. Many want to work not just for money but for a purpose. However, highly competent people want jobs that allow them to innovate, but the education ecosystem often kills innovation.”

Najelaa believes we have become our worst enemy in the effort for better education. In various occasions, she calls herself “a victim of public education.”

“When I say I am a victim of public education, when I say the educational system in our schools is not functioning well, the benchmark is not just the results of national assessments or PISA measurements but all the problems we encounter. Not only in Indonesia but worldwide. In Indonesia specifically, the issues are related to the environment, waste management, corruption, character issues, and values.”

She also affirms that education has become a self-validating system where quality is only measured by GPA or acceptance into good universities. The key to this issue, says Najelaa, lies with the actors within the education ecosystem. Schooling should aim to develop real-life competencies, not just progress through stages.

“This requires behavioural changes from everyone in the education ecosystem. As seen in many countries, this cannot happen with just one policy or by solely relying on the government. Everyone must work together. Even if teachers were perfect, there would be no change without active parental involvement. Parents are the primary and foremost teachers; without their engagement, there will be no change.”

Digital innovation for inclusive education

On the topic of digitalisation, Najelaa says she appreciates the government’s efforts to improve connectivity. She believes the current digital divide is now more about digital literacy—recognising quality content, English proficiency, and critical thinking to identify reliable sources—rather than just access to the internet and devices.

To leverage technological advancements, Najelaa and her colleagues established Sekolah Murid Merdeka–SMM [Independent Students School] in October 2019. It was the first in Indonesia to introduce “blended learning,” combining in-class and online education. Within a few years, SMM expanded to more than 40 branches nationwide.

“SMM aims to provide affordable, high-quality education with a focus on quality, flexibility, and personalisation tailored to each child’s needs. This is achieved through the optimal use of technology, which enhances teachers’ abilities to manage, analyse, and address student needs efficiently.”

Before COVID-19, Najelaa admits, many parents were sceptical about blended learning. Parents doubted whether their children could concentrate and how it would affect their social skills. “However, when we were forced to move online due to COVID-19, our student numbers reached thousands in such a short time.”

“We noticed that parents who questioned online learning had previously experienced poor-quality online education. I cannot blame them for being traumatised by it due to poor learning design. Meanwhile, at SMM, many students continued not just because they were forced to during COVID-19, but because they received a quality education.”

At the heart of digitalisation, Najelaa adds, is inclusion. She stresses that education should be for life, fostering empathy, understanding, and effective communication among diverse individuals.

“If inclusive schools accommodate children with disabilities, the ones who truly benefit are not just the children with disabilities, but their peers as well. Inclusive education helps children appreciate each other’s uniqueness, see people as whole individuals, develop empathy, and communicate according to their peers’ needs. It’s an incredible experience.”

She regards the issue as not just a lack of capacity but a lack of commitment. Najelaa often expresses frustration when fellow administrators claim they can’t accommodate students with disabilities.

“Make it happen,” she urges. “As educators, we must set an example. Inclusivity must be taught during children’s developmental years; mere advice later won’t work. Without direct experience, they carry stigmas and labels into adulthood, affecting their workplace and societal interactions. It’s not the people’s fault, but the bridge they were provided with.”

As the conversation ended, Najelaa called for more collaboration between ASEAN countries. “We know there are many good examples from Singapore, Viet Nam, Malaysia, and other countries, specifically in areas such as bilingual education and entrepreneurship. Let’s create communities that share best practices and spread good initiatives across ASEAN countries, including examples from Indonesia.”

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the interviewee and do not reflect the official policy or position of ASEAN.