Inclusive education for all students, including those with disabilities, is high-quality education that not only teaches students valuable skills but also fosters a sense of belonging. Inclusive education is necessary at preschool, primary, secondary, and post-secondary school; technical and vocational training; lifelong learning; and extracurricular and social activities.

Students with disabilities who are included in school are healthier, can apply their skills to other settings, look forward to going to school, and are more likely to be civically engaged and employed later in life.

A root cause of exclusion in education is discrimination. It may be based on poor legislation, cultural stigma, or lack of training in the education system on the methods and value of inclusion. Therefore, inclusive education requires transformation of not just policy but also culture.

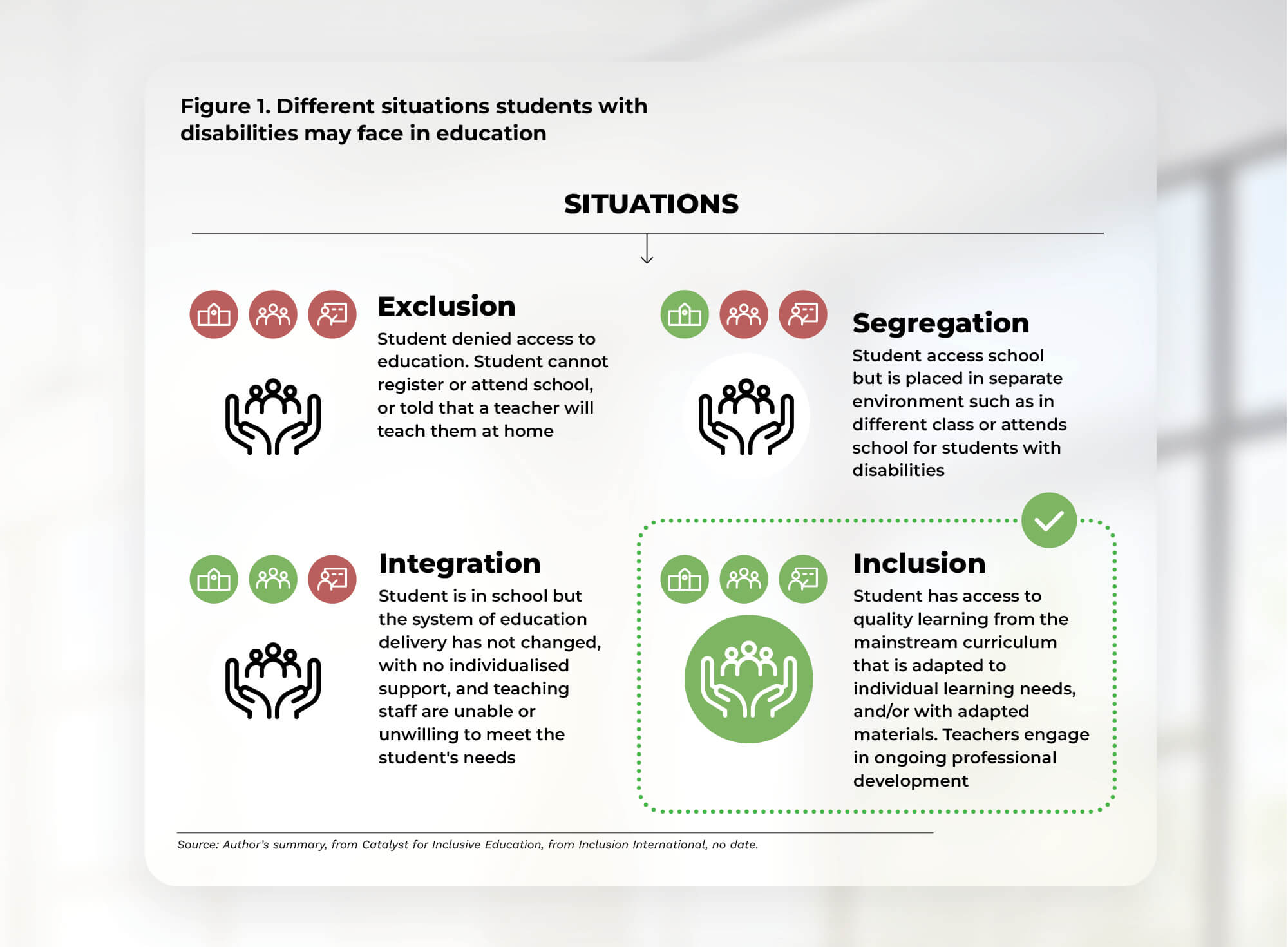

Inclusive education is not just for students with disabilities, as “inclusive education is central to achieving high-quality education for all learners, including those with disabilities, and for the development of inclusive, peaceful and fair societies” (UNCPRD Committee, 2006). Figure 1 outlines the important differences between exclusion, segregation, integration, and inclusion.

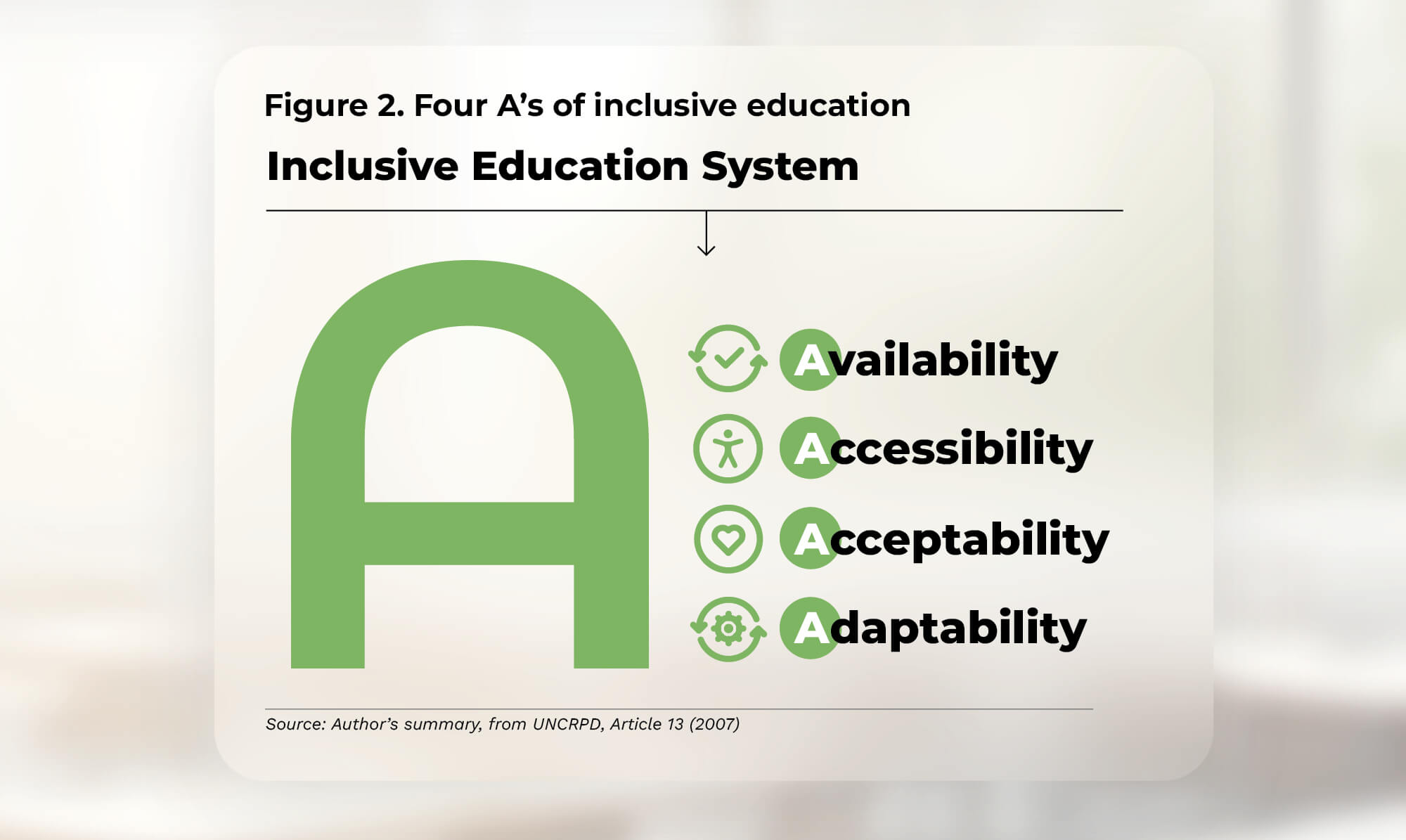

Placing students with disabilities in the classroom without support, providing separate classrooms for them, teaching them only at home, or denying them entry to the school system is not inclusion. An inclusive education system is a long-term, national, or regional commitment to uphold the rights of students with disabilities so they do not face discrimination. Figure 2 shows the four interrelated features of inclusive education systems (UNCRPD, 2007) that can offer tangible changes in the classroom such as modifications in content and teaching methods.

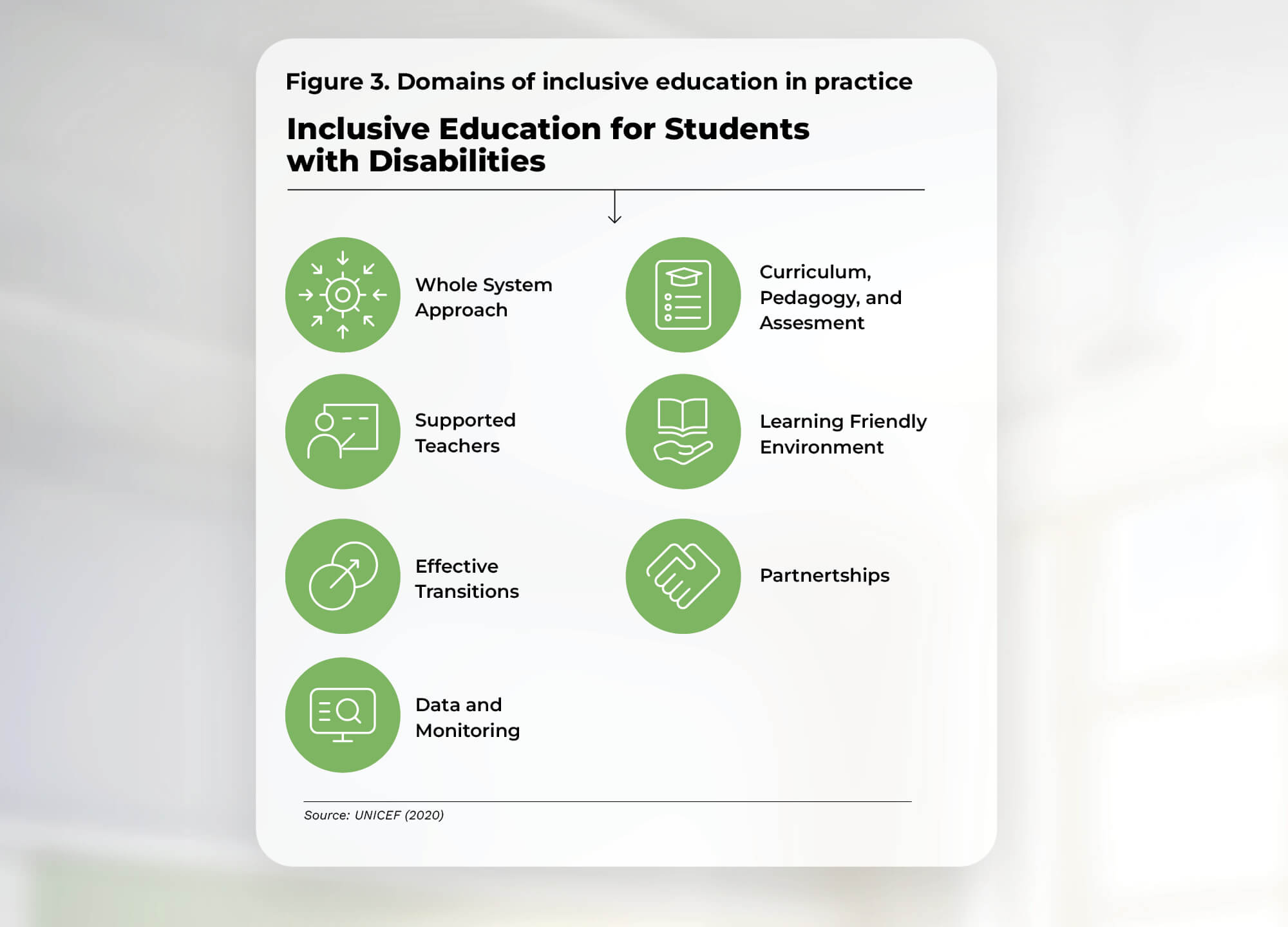

Domains of inclusive education

Students with disabilities can be included in education through several entry points. Figure 3 shows interrelated domains that form a system of inclusive education. A comprehensive review of the domains and the metrics to measure a country’s position and set goals for growth can be found in UNICEF’s (2020) Education for Every Ability.

Equitable education involves varying degrees of factors that allow students from different learning and cognitive backgrounds to learn together. Equitable does not mean equal or the same learning methods. Therefore, some level of individualisation of teaching may be needed to teach all students effectively. Support can be used rarely, sometimes, or always for long-term intervention.

1. Whole-systems approach

Article 4 of the UNCRPD calls on states to adopt a whole-systems approach to inclusive education, which refers to the responsibility and ownership of their role across stakeholders (UNICEF, 2020). The approach uses laws and policies that explicitly state that children with disabilities should receive quality education. The approach also involves inclusive leadership and culture at all levels of the education system, and a national plan that guides the implementation of goals and strategies to fully include students with disabilities. Resources should be properly allocated, and stakeholders can work together to shift attitudes, policies, and practices by tackling negative attitudes towards disability through institutional capacity-building and awareness programmes.

2. Curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment

Good progress has been made in the physical environment and in information communication and technology (ICT) such as closed captioning on television shows or accessibility of public documents. Less effort, however, has gone into making education curriculums accessible to all (UNESCAP, 2018). Flexible curriculums, teaching methods adapted to the learner’s style and needs, and increased use of formative assessment based on competencies rather than benchmark achievement can open the curriculum to students with disabilities with a fundamental paradigm shift: curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment should focus on a student’s capacity and aspirations and not just on content. Assistive and adaptive technology along with reasonable accommodation can help students with disabilities gain access to curricular competencies (UNICEF, 2020).

Universal design for learning (UDL) is a system of pedagogy and assessment, the curricular expectations of which apply to all students in the classroom, from the highest achieving to the one who needs the most support. UDL has been successfully modelled in various countries. It captures the why in learning through engagement, the what of learning through representation, and the how of learning through action and expression (CAST, 2018).

3. Supported teachers

Teachers are at the heart of learning in classrooms and crucial in implementing inclusive education. Their competency, motivation, and attitudes towards students with disabilities make a significant difference in learning outcomes and sense of belonging in schools. Whilst they can make a positive difference in the lives of students with disabilities, teacher training programmes do not always provide adequate knowledge about disabilities and ongoing professional development opportunities to use evidence-based methods in the classroom, even though the UNCRPD requires governments to train pre-service and in-service teachers and other support staff in inclusive values and competencies. Such training can help make teachers agents of change, as government policies can be vague at times.

4. Learning-friendly environment

A safe and supportive learning environment can have positive effects on learning outcomes: the brain can receive and process information more productively than when it is in a state of extended stress. The government’s role in ensuring a friendly environment is understated. The UNCRPD mandates governments to create environments that foster inclusive learning for students with disabilities. A school culture of inclusion can help open conversations, interactions, and collaborative problem solving (UNICEF, 2020).

5. Effective transitions

Lifelong learning is fostered through effective transitions between school environments, from preschool to primary to secondary, and from secondary to vocational and tertiary education, and eventually to the job market. In creating a plan for inclusion, educators must consider student’s views, goals, and interests; their protection and safety; and their right to education and health.

6. Partnerships

Education in school systems provides foundational skills to connect with other parts of society such as recreation centres, community libraries, and local transit systems, amongst others. Wherever a student with a disability is placed, in or out of school, is a learning environment. A multi-sectoral and multi-ministerial commitment and a system that holds governments accountable can ensure that legislation and policies are inclusive. Partnerships between governments and civil society organisations can encourage OPDs that can advocate making communities more inclusive. Partnerships can refer to home support through parent involvement in a student’s learning plan and implementation.

7. Data and monitoring

Reliable data on the number, type, and severity of students’ disabilities can help governments, schools, and teachers prepare for successful inclusion. A medical model of collecting data may be helpful when congenital or developmental delays are detected. However, a holistic method of collecting data on disability type, limitations, and, importantly, strengths can help guide stakeholders positively and constructively in making curriculums, pedagogy, and assessments more inclusive, whilst shifting the view of students with disabilities from “other” to “belonging”. Monitoring and evaluation should be done regularly to ensure accountability of programming and government commitments.

One of the key components of data and monitoring includes asking the right question to gather data that captures metrics for reporting. Box 1 highlights the development of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics, which aims to address this issue.

Note:

This piece was reprinted from a 2022 ERIA study on ‘Inclusive Education in ASEAN: Fostering Belonging for Students with Disabilities’ authored by Rubeena Singh. It was prepared under Giulia Ajmone Marsan’s (ERIA) supervision with inputs and support from Lina Maulidina Sabrina (ERIA).

Access the study from the following link: https://www.eria.org/publications/inclusive-education-in-asean-fostering-belonging-for-students-with-disabilities/

Washington Group on Disability Statistics

The Washington Group on Disability Statistics is a City Group sponsored by the United Nations and, in 2001, commissioned to improve the quality of data on disability and its international comparability. The Washington Group promoted and coordinated international cooperation in health statistics, with a focus on disability measures appropriate for census and national surveys.

In 2016, the questions in the Washington Group/UNICEF Child Functioning Module were finalised for use in national household surveys and censuses. It assesses functional difficulties in children aged 2–17 across vision, hearing, communication and comprehension, mobility, emotions, and learning. The functionality of each is assessed by providing questions on a rating scale.

Questions are different for children 2–4 and 5–17 years of age and are in English, French, Spanish, Vietnamese, Russian, Chinese, Arabic, Portuguese standard, Portuguese Brazilian, and Khmer. The questions provide information that can be compared and analysed for factors affecting learning that are not otherwise captured in medical data.

The database can be used to understand reasons for limited participation in an unaccommodating environment and offer insights to improve opportunities for persons with disabilities, even if they have not been officially diagnosed (UNICEF, 2017). A few countries in this report use the Washington Group questions to collect data on persons with disabilities.

Source: UNICEF, 2017