In 1996, Rusdy Rukmarata and his wife Aiko Senoesenoto founded Eksotika Karmawibangga Indonesia or EKI to nurture young dancers and enable them to earn a decent living.

EKI built a dance studio and dormitory for its students and offered courses in traditional dances, modern ballet, jazz, hip-hop, and even vocal and English language training. It was the country’s first professionally managed dance company that paid fees, allowances and insurance to its members. Several of its original dancers, now in their 50s, are still actively performing.

For over 20 years, EKI has produced musicals and shows that are modern but distinctly Indonesian. Rusdy, EKI’s Artistic Director, says most of Indonesia’s traditional dances and performances are rooted in local stories and communities, with themes revolving around people’s everyday concerns.

“There are Indonesian musicals called Blantek or “blank text.” It means there is no script so that the duration can be one hour, but it can be four hours. It’s really fun to watch, but for modern audiences, they can’t sit through it.”

EKI adapts traditional themes and creates scripted performances that appeal to a wider and younger audience. One of its most popular productions, EKI Update, is a series of variety shows that combine dance numbers with quizzes and interactive games and is now viewable online.

“It is more people-based and young and based more on the appreciation of people, not the artist. First, when we started EKI, I just came back from the London Contemporary Dance school, so the vision was more like from the view of the artist and how to communicate using the language of the art of dance and theatre but now because we go back to the roots of the Indonesian traditional arts, it was more communicative.”

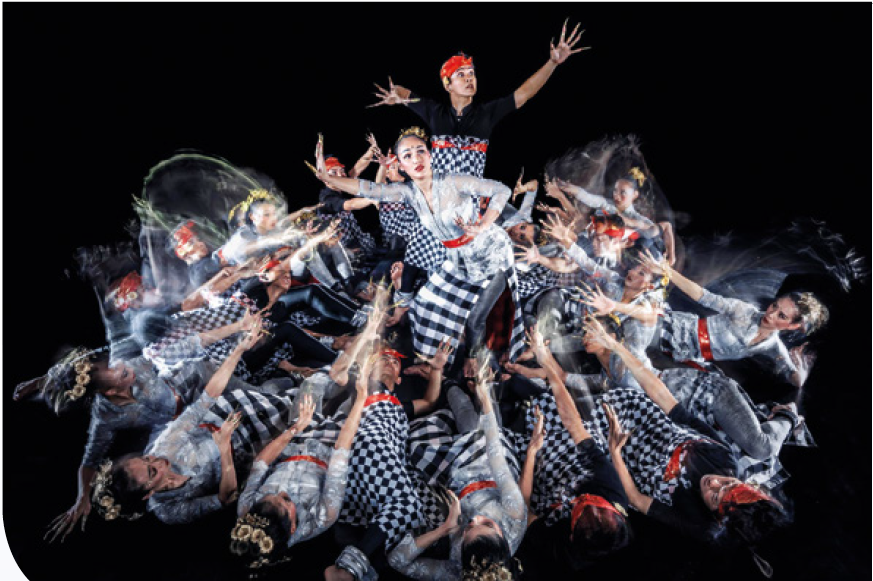

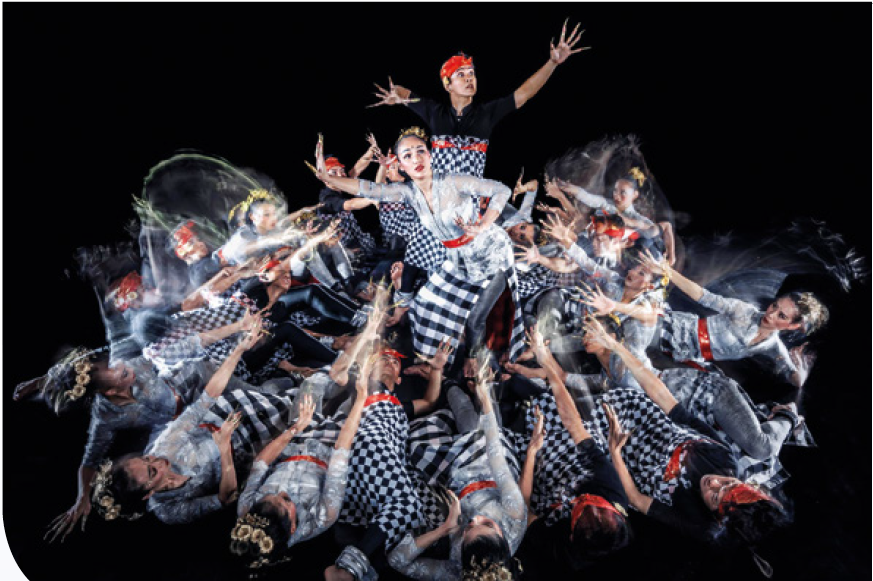

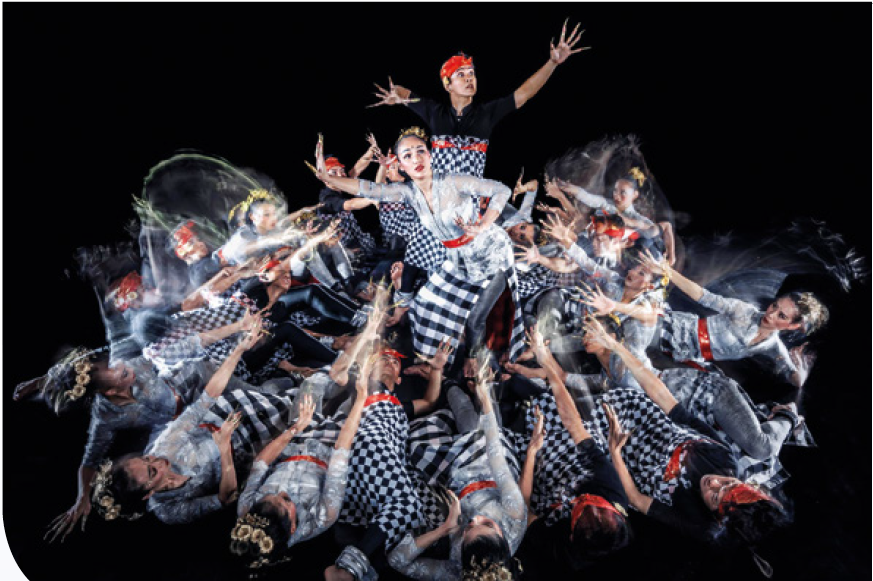

“Along with the times, EKI’s stage musicals also use various special effects that produce works such as shadow dance, interactive dance video, LED dance and others. During the pandemic, because it could not be performed on stage, EKI’s musical works entered the realm of film, using various

cinematographic effects as well as digital effects using green screens and also game applications,” explains Rusdy.

EKI now has 26 dancers and 55 full-time and part-time staff who provide services from stage and broadcast production to set design, and event management.

The pandemic led to many event cancellations, but business is slowly coming back as Indonesia eases restrictions. The upside, Rusdy says, is that the crisis accelerated the company’s digital adoption.

EKI has streamed some of its content on apps like GoPlay. Soon, its online dance courses will be available on several e-commerce platforms like Tokopedia, one of Indonesia’s largest. The online courses are in support of the government’s assistance program for cultural workers affected by the pandemic.

“We see the traditional dancers, who usually dance for weddings and other ceremonies, and have lost their jobs. So, if they can learn modern dance, maybe there will be more job opportunities for them, and upgrade their skills.”

Rusdy appreciates Indonesia’s push to support creative industries but believes much more can be done.

“The arts are still under the Ministry of Arts and Culture, but the Ministry of Industry has to be involved. The Ministry of Creative Industries is a new step. Actually, what we need is to make an industry out of the performing arts. Music recording is already there. Movies are already there. Performing arts is not an industry yet. There are no producers. They don’t have a vision yet of maybe creating something like (London’s) West End.”

“Maybe funding from banks should be available so people will invest in the performing arts. But, it’s not regulated yet. Once, we tried getting insurance for our dancers because they had to do an acrobatic performance, the insurance company needed to create a special package for it.”

Rusdy says Indonesia can learn much from the South Korean model. “K-pop did that; now they have money to put into traditional arts. To survive, you have to put modern dance first, and then generate money and use it to preserve the traditional arts. The government is investing too much on traditional arts, but there are no audiences for that in Indonesia. The audience in Indonesia is modern, especially the youth,” Rusdy points out.

“The government needs to modernise the art institutions, the academies. The art academies in Indonesia are either too traditional or too contemporary, or experimental in style.”

“The young people who are spearheading these new musicals graduated from abroad. They come back so that they are not too Indonesian anymore. But in a sense, that’s what the government needs to do, bring in western teachers here so that we can combine our styles. Teachers from Broadway, West End can help build an academy here. That’s actually our dream in EKI, to create a performing arts academy.”

For its 25th anniversary, EKI launched an online short film about its earlier productions and a sneak peek of a new musical, “Ken Dedes.” Plans are also underway to build EKI’s digital assets and adapt to audiences’ shifting demands.

“After the pandemic, performances will be more like gatherings. It will not merely be a show, but more like an event that people attend. So, we see that as a new opportunity.