The phenomenon of population ageing is emerging as a critical demographic trend with far-reaching socio-economic and policy implications worldwide. By 2050, the global population aged 65 years and above is projected to reach 1.6 billion (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2023). In India alone, the older population is expected to rise to approximately 346 million, while in the ASEAN region, the population aged 60 and over is projected to reach 149 million (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.). This demographic transformation poses complex governance challenges, including rising old-age dependency ratios, shifts in disease burden towards non-communicable diseases, and changes in consumption and labour market dynamics. Among the strategic responses required to address these challenges, designing and implementing comprehensive social protection systems emerge as a key priority. This article examines the evolving realities of ageing in ASEAN and India, explores the intersection between ageing and economic development, and analyses the current status of social protection frameworks across these countries.

Challenges of fast-ageing societies

There is a linear relationship between GDP per capita and the level of ageing (Bloom & Finlay, 2009). Notably, developing countries—including India and many ASEAN Member States—are ageing at a much faster pace than developed nations. This shift gives governments less time to adjust and implement comprehensive policy frameworks before a significant portion of their population reaches retirement age. By 2050, older persons are projected to account for more than 20 per cent of the total population in many ASEAN countries and India.

Ageing societies face multi-dimensional challenges. Women, who tend to live longer than men, often encounter compounded disadvantages due to a lifetime of experiencing gender inequalities. This contributes to the feminisation of ageing. There is also a marked shift in disease patterns towards non-communicable diseases (NCDs), along with rising levels of co-morbidity, multi-morbidity, and declining cognitive capacities. Economic consequences are equally pressing. Ageing leads to reduced labour force participation, increased financial dependency, heightened poverty risks, and escalating healthcare expenditures. The digital divide— exacerbated by limited access to digital devices, inadequate digital literacy, and sensory decline—further marginalises older persons in an increasingly digital world. Given these challenges, the readiness of governments to implement comprehensive senior care strategies that address health, social, financial, and digital inclusion would be key in mitigating the impact of changing demographics.

Social protection programmes in India and ASEAN

Social protection is defined as preventing, managing, and overcoming situations that adversely affect people’s well-being (UN Research Institute for Social Development, 2010). While the term may be interpreted differently by each country, it typically refers to three pillars that society provides to protect its population against economic and social distress, including social assistance, social insurance, and labour market programmes, according to OECD. It, therefore, consists of policies and programmes to reduce the incidence of poverty, unemployment, sickness, and disability and requires fiscal and administrative capacities, as well as policy coordination across multiple sectors and organisations.

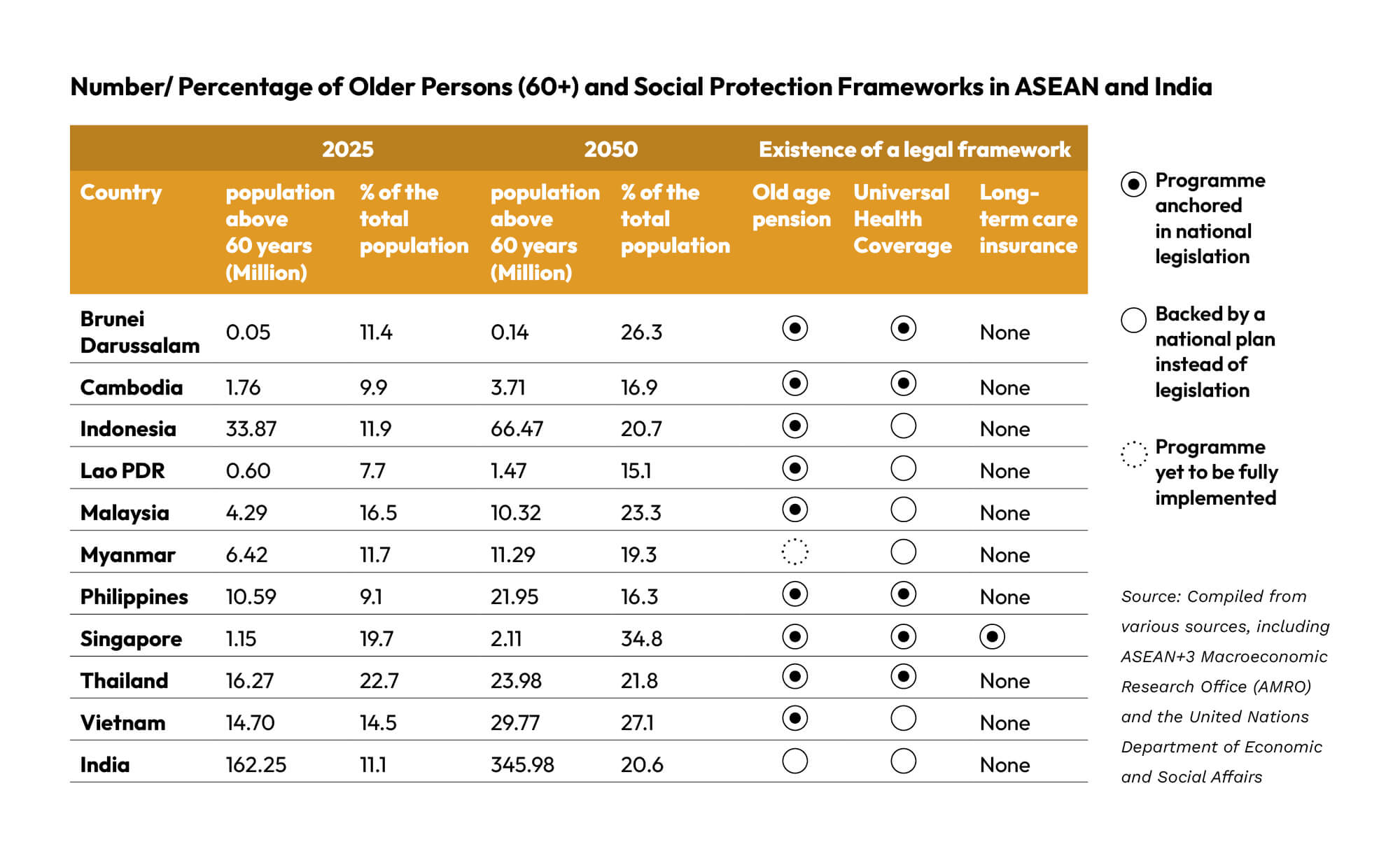

Old-age social protection systems across ASEAN and India are very diverse and characterised by distinct stages of maturity and institutional arrangements (see Table). Legal frameworks across these three areas—old-age pension, universal health coverage (UHC), and long-term care (LTC) insurance—exist in varying degrees, with Singapore having the most comprehensive scope of legal coverage. In ASEAN, except for Lao PDR, all economies offer some form of pension floor, which guarantees minimum income security for seniors (ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office, 2024). ASEAN countries primarily rely on tax-financed non contributory schemes for the pension floor. Another protection programme that aims to provide income replacement in old age is either a provident savings fund or pension fund with defined contribution or defined benefit schemes. Except for Myanmar, all ASEAN countries have introduced national pension schemes for private sector workers, although member contributions finance the schemes. Universal health coverage is another form of insurance that many countries have implemented. In the case of long-term care, Singapore is the only economy to have institutionalised LTC insurance through the CareShield Life and LTC Bill in 2019.

India has several social protection programmes, although not always anchored in specific legislation. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare launched the National Programme for the Health Care of Elderly (NPHCE) in 2010–11 to provide accessible, affordable, and high-quality long-term, comprehensive, and dedicated care services to older people. The Ministry of Rural Development administers the National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP), which provides social assistance benefits to vulnerable groups, including seniors. As of December 2020, more than 28.5 million senior citizens were receiving social pensions under the NSAP (NITI Aayog, 2024). Other programmes include the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly (NPHCE), Pradhan Mantri Vaya Vandana Yojana, Varishtha Pension Bima Yojana, Atal Pension Yojana, Ayushman Bharat–PMJAY and Ayurswasthya Yojana. Other programmes include Atal Vayo Abhyudaya Yojana (AVYAY), which consists of the Integrated Program for Senior Citizens (IPSrC) and Rashtriya Vayoshree Yojana’ (RVY), which are livelihood and skilling initiatives for senior citizens.

Conclusion and the way forward

ASEAN and India’s rapidly ageing populations demand urgent and comprehensive policy preparedness. Ensuring social protection for seniors requires easy access to publicly provided, affordable, and quality social services across health, income security, and long-term care. However, governments often face the twin constraints of limited fiscal space and administrative capacity, especially when responding to the competing demands of large and diverse populations. In this context, regional cooperation between ASEAN and India offers meaningful opportunities for mutual learning and capacity building. Collaborative efforts could include the creation of an ASEAN-India knowledge platform on ageing, joint training programmes for geriatric care professionals, and policy dialogues on sustainable financing models for pensions and long-term care.

ASEAN’s experience with community-based eldercare models and India’s initiatives in digital health and social pensions can serve as reference points for cross-learning. India’s efforts at a holistic approach to elderly care, which harnesses the strengths of traditional medicine systems, is one such example of cross-learning. VayoMitra, i.e., Ayush Geriatric Healthcare Services, is a public health programme that utilises India’s traditional medicine systems, such as Ayurveda and Yoga, for addressing geriatric care. Similarly, Singapore’s LTC scheme, introduced through the CareShield Life and LTC Bill in 2019, may serve as a case study for replication. As both ASEAN and India navigate the demographic transition, such collaborative mechanisms can help build resilient institutions and people-centred policies to safeguard the well-being of their ageing populations.

Namrata Pathak holds a PhD from the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her research interests include issues in the pharmaceutical industry, particularly in the context of Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), traditional knowledge and biodiversity. She is a Consultant at RIS, Coordinator/Member Secretary of the Forum on Indian Traditional Medicine (FITM) and Co- Editor of Traditional Medicine Review.

The ASEAN-India Conference on Traditional Medicine was held in New Delhi in July 2023.

The views and opinions in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the policy or official position of ASEAN.