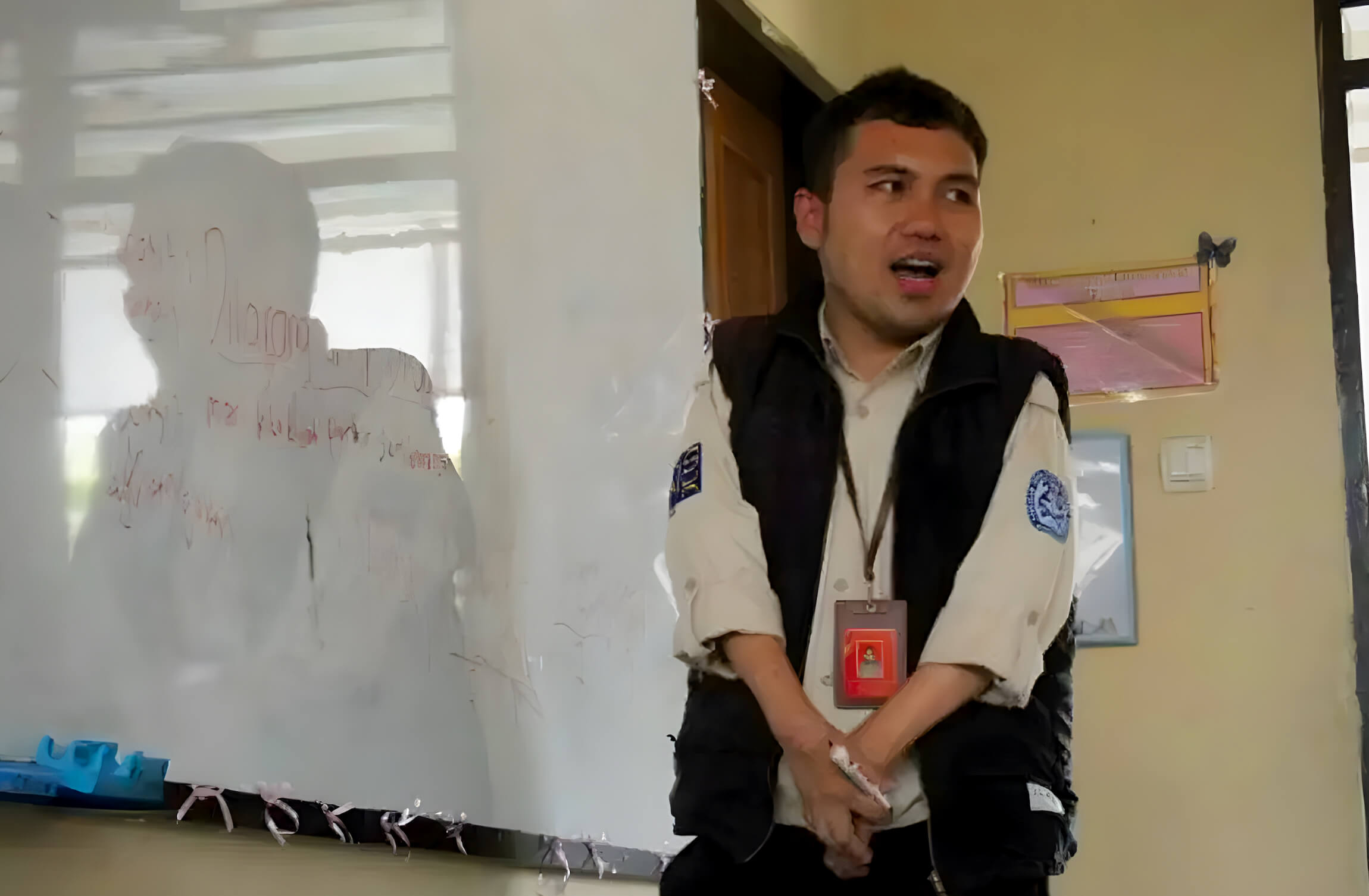

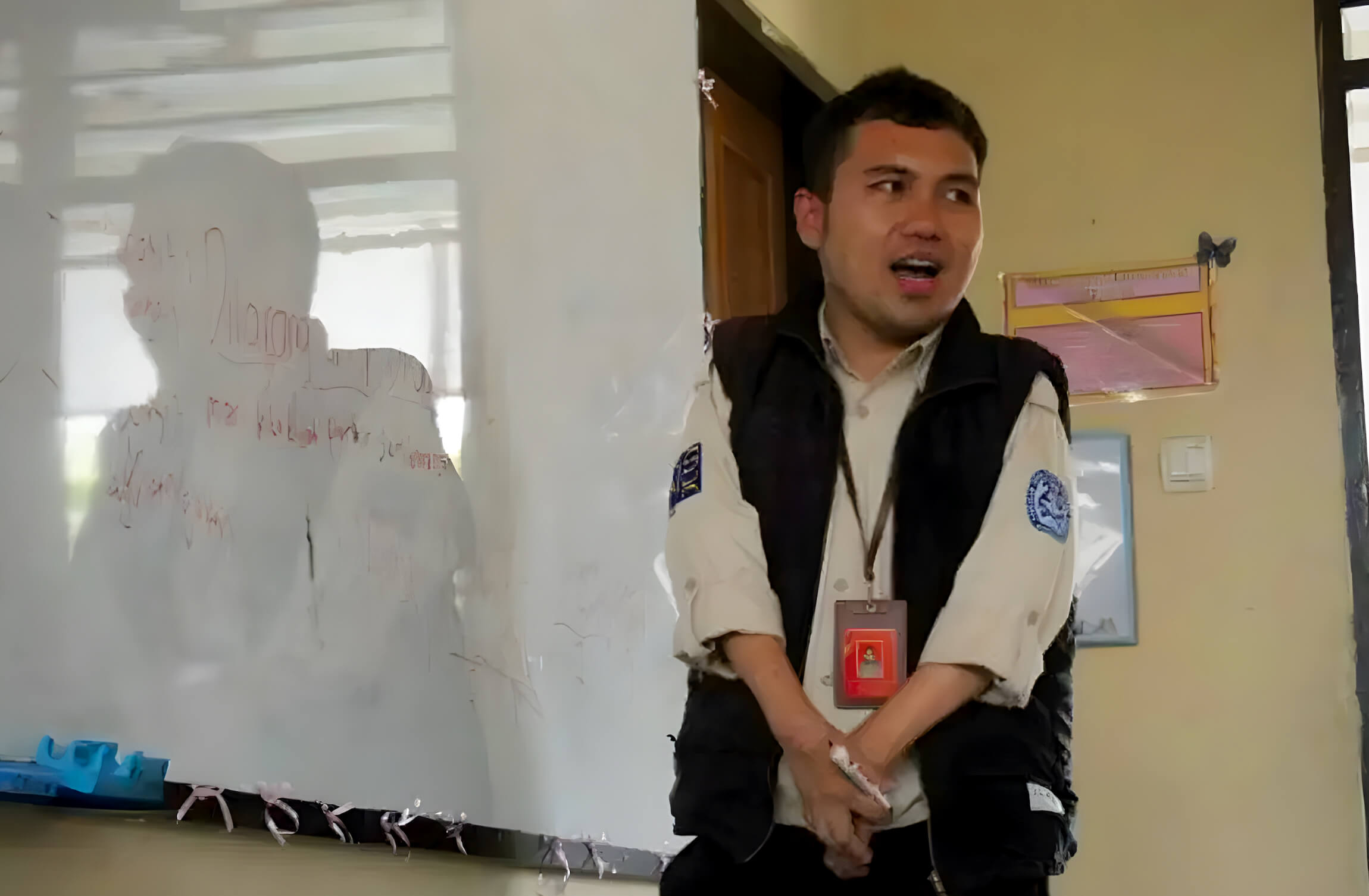

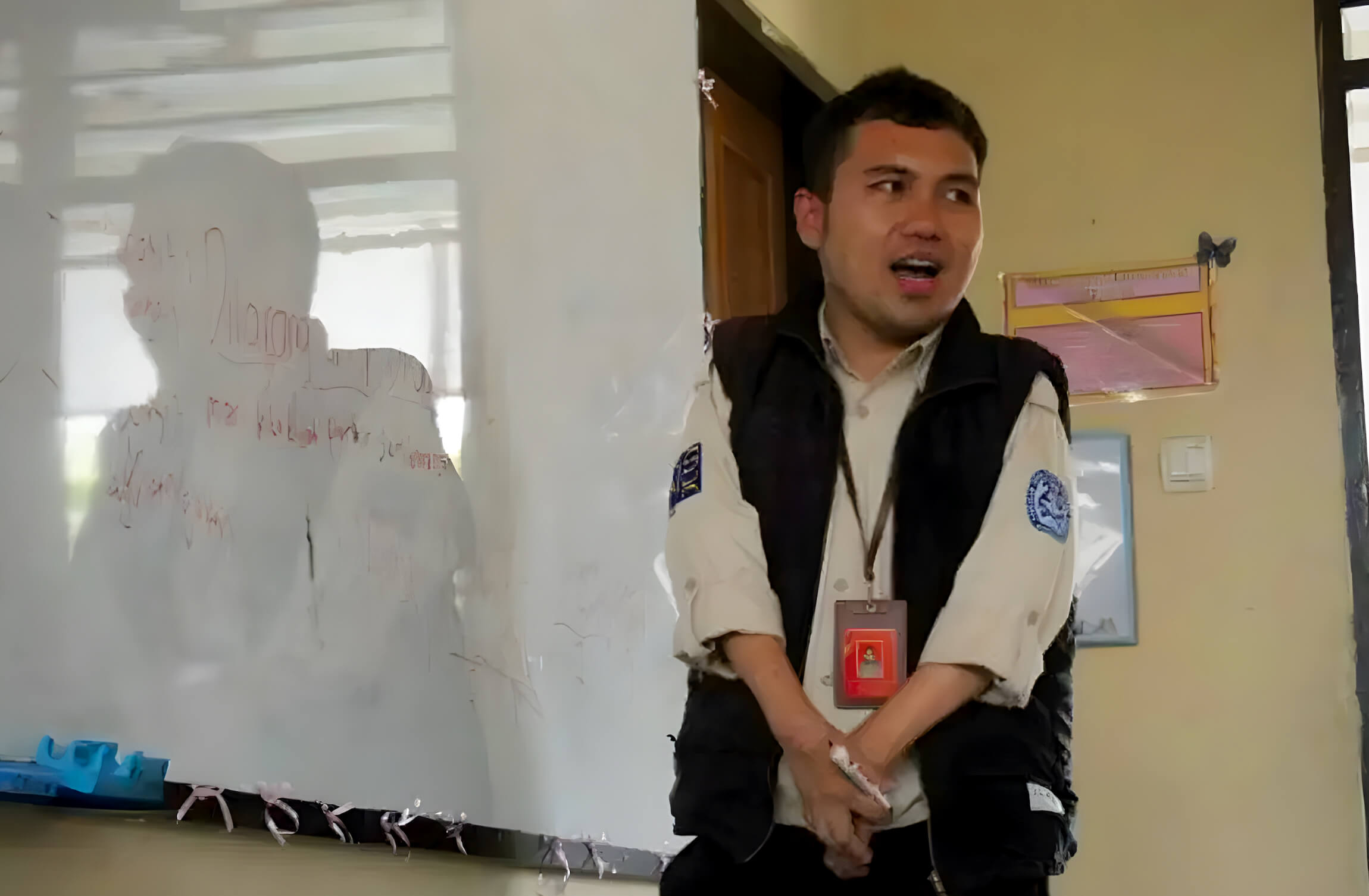

Dadan Mochamad Rhamdan, or Damar (35), is an Indonesian Language and Literature teacher at SMP Negeri [Public Junior High School] 20 Bandung, Indonesia. He was born with cerebral palsy, which affected the development of his hands. The condition also impacts the left side of his body, limiting its mobility compared to his right.

He abbreviated his name to Damar because it means "lantern." True to its meaning, he hopes to bring warmth and light to those around him while creating a safe space for discussion—for his students and his community.

Although he never originally planned to become a teacher, Damar grew to love his career. He says that his students now ignite the fire within him.

Damar’s eyes beam with pride whenever he talks about his students. As part of the Division of Student Potential Development, his responsibilities include coaching and accompanying students in various championships. These competitions include poetry, videography, debate, and even esports like Mobile Legends.

In 2022, Damar felt even prouder when he stood alongside his students, Fadil Nur Saleh and Adam Harisma Dolf, who had just received trophies for their achievements in the Sundanese script and debate competitions, respectively.

“We made a pact because all three of us were competing in different events. We promised to hold our trophies together. And it was an incredible feeling to be able to do that,” he tells The ASEAN tearily.

Damar started teaching in 2019 after failing six times to pass the civil servant selection test. From 2013 to 2018, he kept applying for a civil service position while working as an administrator at an educational institution. Later, he moved to Purwakarta, West Java, to work as medical records staff at a healthcare facility.

“I only worked in Purwakarta for six months. During that time, I lost 12kg. Honestly, I realised I needed to be home—I still rely on my family for certain things,” he says.

He explains that his acceptance was made possible by a national policy mandating that at least 2 per cent of civil servant positions be allocated to people with disabilities. Just three years after beginning his career as a school teacher, Damar was recognised as one of Bandung’s outstanding civil servants.

Damar initiated Ruang Edukasi Inklusi [Inclusive Education Space], an inclusive education platform at his school that fosters awareness and understanding of disabilities among students and staff. His efforts in advocating for inclusivity have earned him recognition as an outstanding civil servant.

“The award was like a gift to my parents. It symbolises my gratitude for their trust, support, and the opportunities that have shaped my path to where I am today.”

Growing up, Damar attended regular schools near his home in Cicalengka, West Java. “I was always among the top 10 students. I had to write with my feet and use a special desk, but my teachers never treated me differently. They gave me the same opportunities to participate in competitions, just like my peers. And my friends? They were always there, always supportive.”

After finishing high school in 2008, he faced a hurdle: there were no universities or higher education institutions nearby. After taking a gap year, he finally had the opportunity to continue his studies when a collaborative class programme, offered by Universitas Islam Nusantara Bandung, opened at a local primary school just 5 kilometres from his home.

“My parents were hesitant, but I insisted. I was adamant about continuing my studies. At that time, I wasn’t picky—I was willing to accept any major. If it had been up to me, I would have chosen mathematics or psychology, but the only available option was Pendidikan Guru Bahasa Indonesia [Indonesian Language and Literature Education]. That opened the door to my career.”

Bringing inclusivity to the classroom

Like any teacher, Damar felt nervous on his first day in front of the class. He worried about how his students would react. “This feeling persists even now, especially at the start of a new academic year when I have to introduce myself to a new group of students.”

“Why doesn’t he just teach at a special needs school?” was one of the remarks that stung the most. But comments like that didn’t stop him. “My students have been incredibly supportive. One of them, Ardellio Satrio, even wrote a short story about disabilities and won a national competition.”

The traditional teaching method presents another challenge for Damar. His condition makes it difficult for him to write on the whiteboard, which initially frustrated him. However, rather than dwell on what he couldn’t do, he focused on what he could. He found creative ways to engage his students, using technology, gamification, and interactive methods that made learning more exciting.

Yet, he acknowledges that acceptance doesn’t always come quickly. At first, some of his colleagues hesitated to assign him responsibilities, unsure of his capabilities. “There was reluctance. They weren’t sure whether I could handle the tasks, but over time, as they saw my abilities, that trust naturally grew.”

As time has proven his capabilities, Damar now juggles multiple roles. In addition to being a Bahasa Indonesia and a homeroom teacher, he is part of the Student Affairs Staff, serves as the student council advisor, and mentors the journalism club—and, at one point, even assisted the school’s IT staff.

Damar’s experiences made him realise he doesn’t need to give endless speeches about inclusivity. Simply by being present—by existing in public spaces—his students learn through observation. “They see what inclusion truly means, how to support people with disabilities—not through words, but through action.”

More than anything, Damar hopes that students and teachers with disabilities are not just accepted, but valued, trusted, and empowered to thrive. “We must not just welcome students with disabilities—we must know how to support them,” he says.

Indonesia’s school enrolment system sets aside quotas for students with disabilities, yet many seats remain unfilled. “There’s still a stigma,” Damar observes. “Parents hesitate to acknowledge their child’s learning challenges—dyslexia, slow learning— afraid of labels. But these children belong too.

“Public spaces for us are scarce— whether in education, infrastructure, or daily life. Schools claim to be open to students with disabilities, but many lack the proper support. Some accept children with dyslexia or physical limitations, yet their teachers aren’t trained to accommodate them.”

As our conversation ended, Damar hoped his story would inspire others to create more opportunities for persons with disabilities.

“Open the doors. That’s all we ask. I know this because when I was given a chance, I took it as a responsibility. When public spaces welcome us, we don’t take it for granted—we strive, and we work twice as hard. When access is granted—so many extraordinary abilities will emerge. There is so much we can contribute.

“The media plays a powerful role in this. We aim to amplify our stories, not as charity, but as proof that we are here, that we are capable. How many eyes will read, will see, will be inspired? That, in itself, is an opportunity. Regulations matter, but change begins in the smallest spaces.”

The views and opinions expressed in this conversation are solely of the interviewee and do not reflect the official policy or position of ASEAN.