Demographic transition in ASEAN

The ASEAN region is ageing rapidly: by 2035, the number of older persons aged 60 years and over in the ASEAN region is projected to increase to over 125 million, more than double the 2015 population (ASEAN, 2015). This demographic transition is driven by declining fertility rates, lower mortality rates, and increased life expectancy. It highlights the achievements of ASEAN countries—of economic progress and improvements in public health and living conditions in the region (ASEAN Secretariat, 2024). However, it also brings a host of challenges, including a rise in old-age dependency, decreasing labour productivity, escalating healthcare costs, and strains on pension and social protection systems, among others (ASEAN, 2023; ASEAN Secretariat, 2023; ASEAN Secretariat, 2020).

One notable aspect of this demographic transition is its implications for gender equality. Women, who live longer than men, form the majority of the region’s older population. In 2023, almost 56 per cent of older persons aged 60 years and over and 65 per cent of those aged 80 years and over were women (UN, 2024).

Policymakers in ASEAN face increasing pressure to address these challenges with effective policy responses. This article advocates for reimagining ageing as an opportunity, rather than viewing it as a challenge, so that ASEAN countries can tap into the potential of older persons. However, a crucial element of reimagining the ageing narrative would be to address the gender dimensions, in particular, by rethinking caregiving and employment. The following sections discuss the impact of the gendered imbalance in caregiving on older women and ways to build a more equitable and inclusive future.

The looming care crisis

With higher life expectancy, people are living longer, resulting in increased demand for care. Living longer does not necessarily mean living healthier. There continues to be a gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy (HALE). In 2019, the number of years an older person aged 60 could expect to live in ill health ranged between 3.7 years to 5.6 years in different ASEAN countries (ASEAN Secretariat, 2023). Disabilities are higher in old age, with an estimated 16 million older persons living with an impairment in at least one primary activity of daily living (ADL) and 35 million living with an impairment in at least one instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) in 2020 (Yau et al., 2022). Levels of functional disability also increase with age. A review of studies on functional disability shows that prevalence of ADL disability was higher in those aged 75 years and over (23.1 per cent) compared to their younger counterparts aged 60-74 years (9.5 per cent) (Yau et al., 2022). Older persons are also more likely than younger age groups to suffer from chronic diseases. For example, in 2019, the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases among those 55 years old and above in Southeast Asia was four times greater (23.2 per cent) than among all ages (5.5 per cent) (ASEAN Secretariat, 2023).

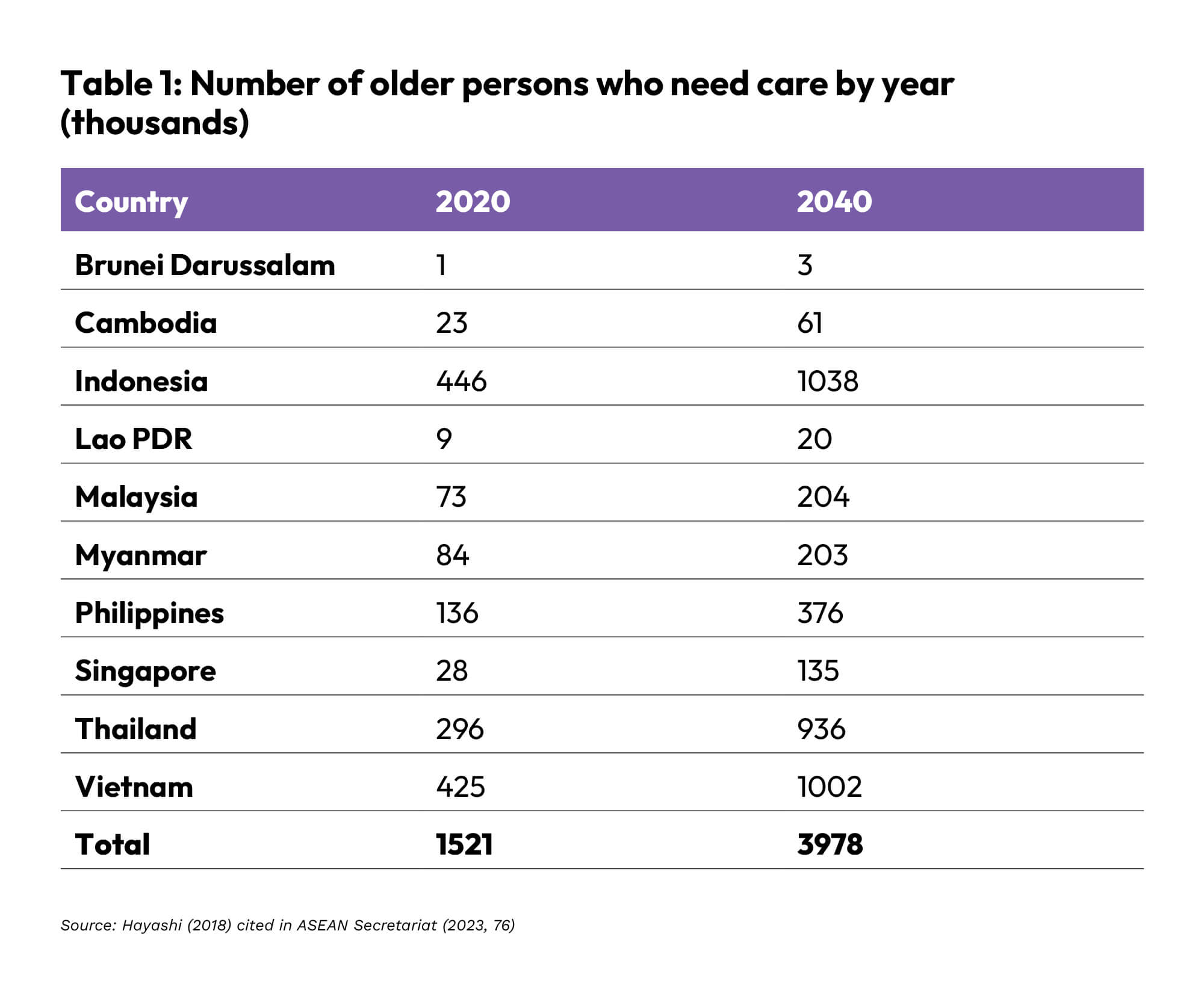

Care needs are expected to double or triple in all the countries in the region in the coming decades (Table 1), raising the question: who will provide this care?

The unequal burden of care and gender inequalities in old age

Governments across the region are grappling with the challenge of addressing this unprecedented surge in demand for care. Current policy responses range from strengthening social protection systems to expanding home-based and community-based care services, as seen, for instance, in Singapore. However, long-term care systems remain underdeveloped in much of the region. In the absence of quality long-term care, older persons continue to rely heavily on family members for care (Harding, Sevilla and Aw, 2020).

Women bear a disproportionate share of the burden of care for older persons. In Viet Nam, for instance, data show that women are responsible for 56 per cent of childcare and eldercare (Counting Women’s Work, n.d). Similarly, a study from Thailand using data from a time-use survey conducted in 2014/2015 found that two-thirds of the sample of 663 caregivers of older persons were women (Bui and Vlaev, 2021).

This imbalance has serious implications for women’s labour force participation. The ASEAN Declaration on Strengthening the Care Economy and Fostering Resilience Towards the Post-2025 ASEAN Community acknowledges that women’s unequal share of caregiving “impacts whether women enter into and stay in employment and on the quality and remuneration of the jobs they perform.” Women’s labour force participation is lower than men’s across all ASEAN countries (ASEAN Secretariat and UN Women, 2024). In Singapore, for instance, residents outside the labour force who cited caring for parents as the main reason for not working were predominantly female (63.4 per cent) and aged 50 and above (Ministry of Manpower, 2025).

Furthermore, caregiving responsibilities affect women’s ability to participate fully in paid employment. Women often choose to work fewer hours (part-time), have shorter working lives or exit the labour force entirely.

The cumulative impact of these gendered patterns of inequality is that when women reach old age, they have less savings and are financially less prepared than men. To illustrate, a 2017 study of low-income professionals in selected ASEAN countries found that the gender retirement savings gaps ranged from 17 per cent in Singapore to as high as 46 per cent in Malaysia. (Marsh and McLennan and Tsao Foundation (ILC Singapore, 2017).

These financial disparities are compounded by the fact that women have greater healthcare needs. A survey of functional disability in ASEAN finds that the prevalence of ADL disability was 2.3 times higher in women than in men (Yau et al, 2022). A higher proportion of women also suffer from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) than older men. (ADB, 2024). For example, the prevalence of hypertension was 12 percentage points higher for older women than for older men in Indonesia and the Philippines (ADB, 2024). The concern is that these healthcare needs are largely unmet, especially for women in low-income households (ADB, 2024; Yeung and Thang, 2018).

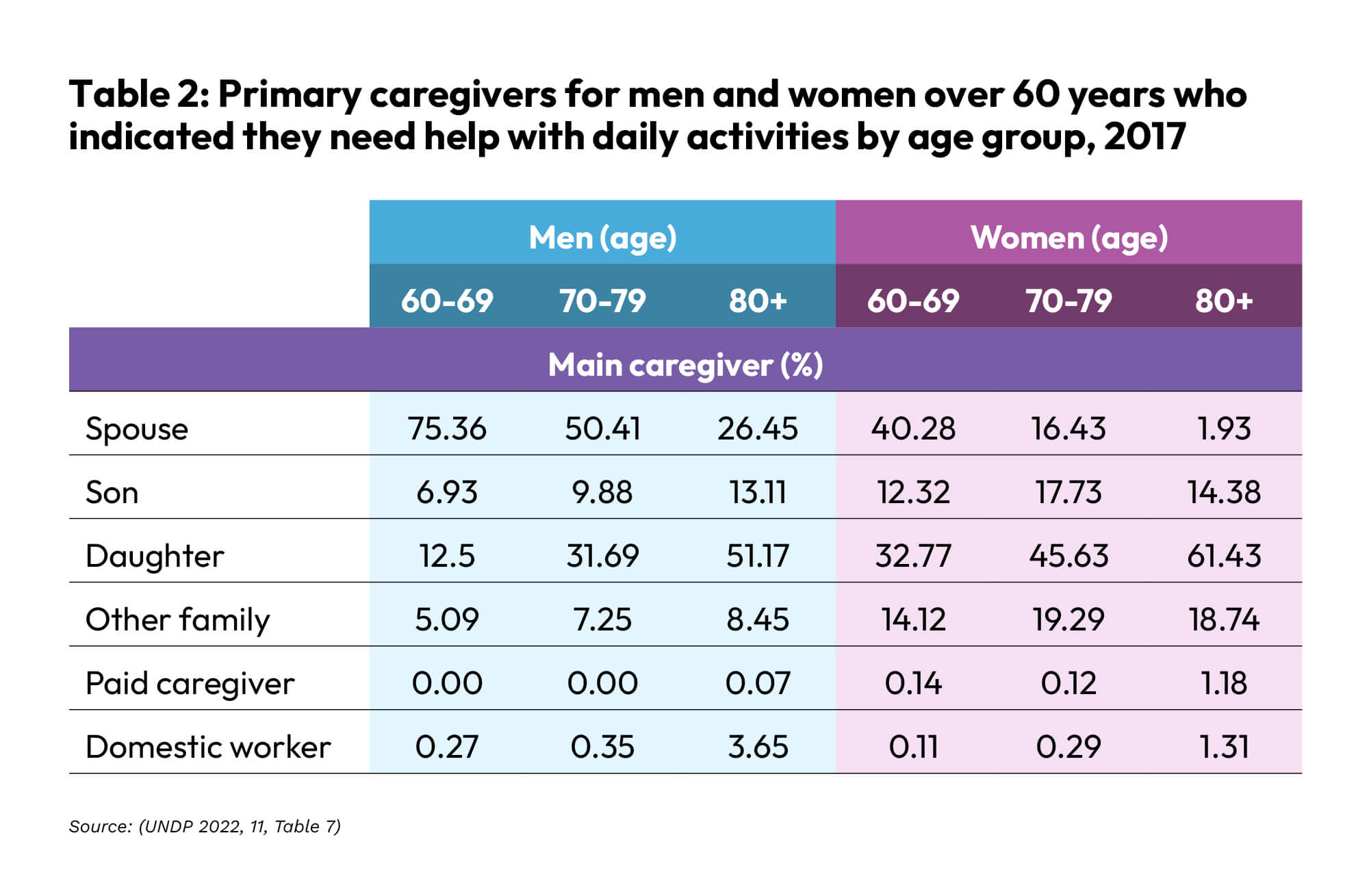

The situation becomes even more acute when older women become caregivers for others, including spouses and parents. A study in Thailand, for instance, shows that the spouse was the main caregiver (75.36 per cent) for men aged 60-69 years (Table 2) but not for women. Despite being in need themselves, older women continue to provide care for others. As the Asian Development Bank (2024) reports, the care crisis in Asia may not be imminent, mainly because “older women continue to provide care into old age.”

Caregiving, employment and financial security for older women

The unequal burden of caregiving puts women at significant risk of financial insecurity in old age. Caregiving imposes both welfare and financial costs. A review of studies of caregivers from Singapore until 2018 reveals that a large proportion of caregivers experienced “caregiver burden” or stress, which reduces their quality of life (Loo, Yan and Low, 2021). Furthermore, another Singaporean study published in 2019 estimates that caregivers of older persons, on average, lose 63 per cent of their income (AWARE, 2019).

To address this compounded caregiver penalty, policymakers must provide greater opportunities for older women. A “caregiver and age-friendly” workplace can help mitigate some of the challenges of caregiving. Estimates suggest that if constraints on older women’s time, mainly caregiving, are removed, older women in several ASEAN countries have significant untapped work capacity. Among women aged 65-69 years, untapped work capacity— defined as individuals with the health capacity to work but who do not—ranges from 22 per cent, 22.5 per cent, to 37.9 per cent in Indonesia, Thailand and Viet Nam, respectively (ADB, 2024).

Intentionally developing inclusive workplaces will also benefit women who are currently working and facing the challenges of juggling caregiving and work. With a rapidly ageing population, the number of workers with caregiving responsibilities is set to grow exponentially: for instance, a survey of six Asia-Pacific countries in 2022 (i.e. Australia, China, Indonesia, Japan, and Singapore) suggests that the proportion of employees who are also taking on caregiving responsibilities (termed “employee-caregiver”) will rise from 100 million to 1.2 billion in 2035 (Thom et al., 2023).

Building a “caregiver and age friendly” workplace

In practice, a multisectoral approach is required to address this complex issue. A variety of policy initiatives at different levels involving multiple stakeholders, such as businesses, governments, workers, unions, and care providers, is necessary. Gender, age, and care perspectives will need to be incorporated into the design of future workplaces, which will have to be coordinated with other elements of the care economy, including building care infrastructure, providing paid care services, and supporting workers with caregiving responsibilities.

Adapting the ‘Triple R’ framework for the Care Economy (Elson, 2017) would be a useful starting point:i) Recognise the value of unpaid care work by workers, particularly older women; ii) Reduce the burden of unpaid care work through workplace policies such as flexible work arrangements and provision of adequate eldercare services; iii) Redistribute the burden of unpaid care by addressing gender-based stereotypes about caregiving roles. This could be achieved through awareness campaigns and training to challenging unconscious biases.

Additionally, meeting the unique needs of older women requires specific policy measures, including skills training, job search assistance, career guidance and initiatives to combat gender and age-related biases in workplace practices, such as recruitment and dismissal (Ministry of Manpower, 2024; TAFEP, n.d.; Thom et. al., 2023).

A valuable tool for developing appropriate policy initiatives would be to establish an ASEAN Workgroup on Building a Caregiver and Age- Friendly Workplace. Along the lines of Singapore’s Tripartite Workgroup on Older Workers (Ministry of Manpower, 2019), the ASEAN Workgroup on Building a Caregiver and Age-Friendly Workplace could review the current landscape of caregiving and work opportunities in the ASEAN region, particularly through a gender and age lens. It can collate best practices from the region and examine the lessons learnt from these best practices. The Workgroup could also look beyond the region to find potential policy solutions and success stories globally and contextualise them to the ASEAN region.

Building a “Caregiver- and Age-Friendly Workplace” will not only enhance gender equality, but it also makes economic sense. If harnessed properly, estimates suggest that the untapped work capacity of older persons (including older women) could raise GDP by 1.1 per cent in Viet Nam and 0.9 per cent in Thailand (ADB, 2024). Conversely, if adequate support is not provided for ‘employee-caregivers,’ it could lead to caregivers leaving the workplace. The survey of employee-caregivers in six Asia-Pacific countries suggests that the cost could be as high as a total GDP loss of 125 billion to 250 billion US dollars by 2035 (Thom et al., 2023).

ASEAN countries are already falling behind in addressing the rapid ageing of their populations in the region. There is no time to wait. Policymakers must act immediately to lay the foundation for a future where older women can participate equally in the economy, fostering a more inclusive and resilient ASEAN.

The views and opinions in this article are solely those of the authors and do not represent the policy or official position of ASEAN.

References may be downloaded from: https://bit.ly/Issue44_Ref