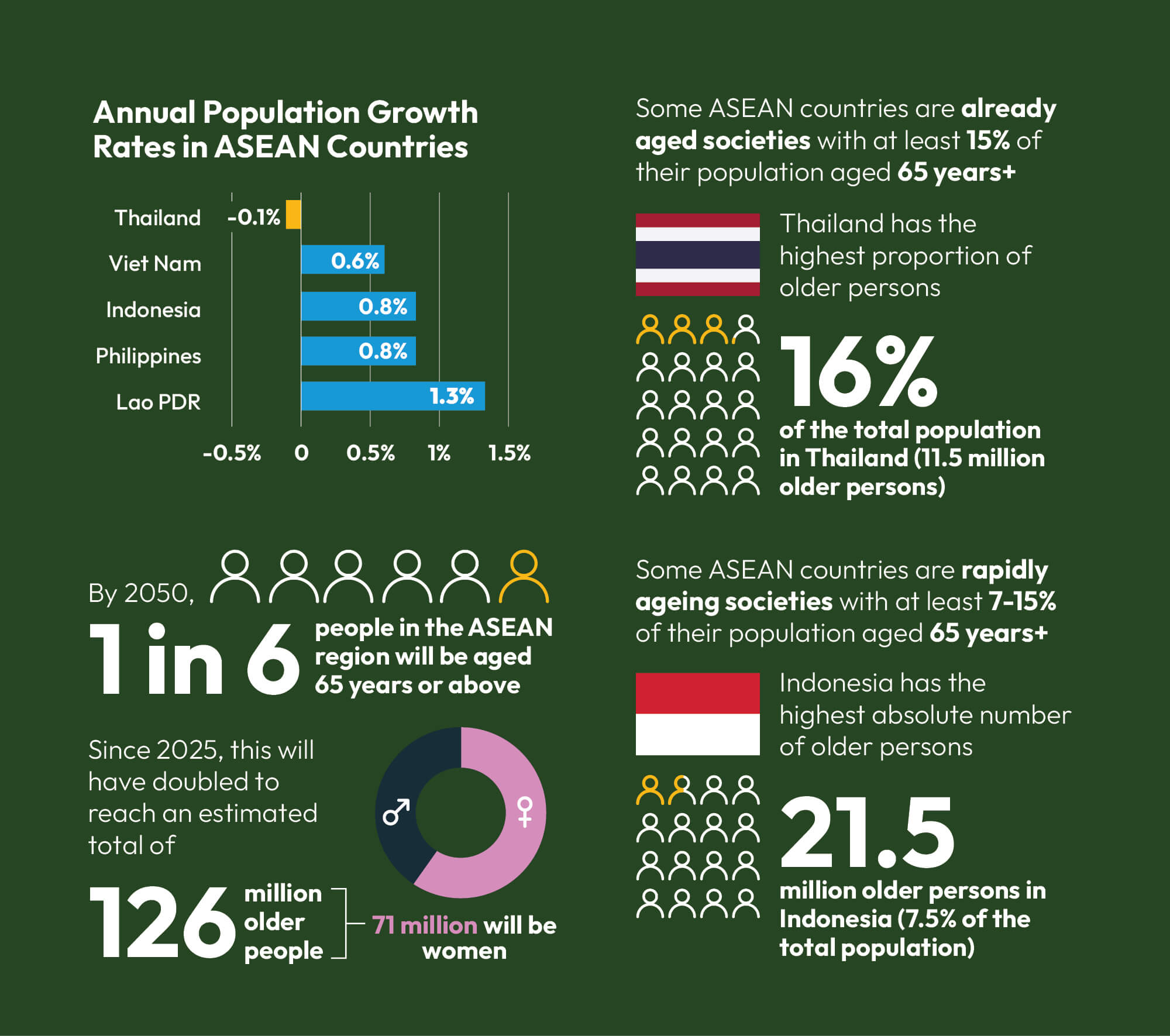

The ASEAN region is undergoing a significant demographic transition. The population of ASEAN countries has grown more than fourfold since 1950, from 164 million to close to 700 million in 2025, and will continue to increase to an estimated 773 million people by 2050. Major changes in population age structures will be seen as a result of this demographic transition, driven by substantial declines in both fertility and mortality, as well as migration.

A decreasing trend in annual population growth rates over the years is observed, even in countries with higher population growth rates (2 per cent growth or more). On the other hand, declining fertility rates combined with increased life expectancy due to lower mortality rates across the ASEAN region are contributing to an increase in the number of older persons.

The physical, mental and emotional challenges of ageing women

For women in Southeast Asia, ageing comes with a variety of challenges. Physically, older women experience many changes in their bodies. The appearance of gray hair and ageing signs on the skin can expose women to gendered ageism—a negative stereotype, prejudice, and/or act of discrimination directed toward elderly people based on their physical appearance, according to Ayalon, et al. (2019). Older women tend to view an aged appearance as a personal failure to maintain their young physique, and believe that looking old renders them invisible or subject to negative treatment, especially in the workplace. For many, an ageing appearance is associated with incompetence, with not having the same energy or vitality as younger women, nor the same strength in memory or capacity to continue to be a productive member of the labour force.

Alongside changes in physical appearance, women also experience menopause. Menopause and perimenopause are a critical challenge for ageing women, and very little is understood about what happens to a woman’s body during the menopause transition. Menopause and perimenopause can last for more than a decade and affect more than 450 million women worldwide at any given time, affecting their health span. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF) Insight Report (January 2025), long-term effects of hormonal changes associated with menopause and untreated symptoms lead to increased risk of chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, neurological diseases such as depression and dementia, osteoporosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and gynaecological conditions.

As women age, they may also encounter mental and emotional health challenges. Some experience anxiety or depression, especially when they drop out of their regular routine of working or caring for their children, and more so if they have to live alone, with no children or living husbands or partners to care for them. Older women are also subjected to specific forms of violence. In Cambodia, Indonesia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, and Viet Nam, national surveys were conducted on the prevalence of violence against women that included older women (e.g., up to age 64). These surveys primarily focus on questions around intimate partner violence (IPV) and sexual violence. However, older women are also at risk of unique forms of abuse, such as “specific forms of economic abuse, or specific acts of physical or psychological violence or controlling behaviors (e.g., physical or chemical restraint), including by perpetrators other than partners,” according to WHO and UN Women (2024).

Extending the age range in standard surveys on violence against women (VAW) helps address urgent data gaps, but surveys alone may not be enough to capture specific forms of violence, potentially underrepresenting the experiences of older women. For example, in Viet Nam, which conducted its second national VAW prevalence survey in 2019, findings indicated that while older women aged 50+ had higher than the national average lifetime rates of violence, their current experiences (in the last 12 months) were lower than for women in the younger age groups. Although younger women experience certain forms of violence disproportionately, it is crucial for data users to understand that standard VAW surveys do not usually capture the unique abuses faced by older women.

The gender gap in life expectancy and its social and economic challenges

In nearly all countries of Asia-Pacific, the proportion of women aged 65 and older who are living alone is higher than among men (UN Population Division, 2022). The gender gap in life expectancy in the region has implications for emotional well-being, financial stability, economic status, and care of older women. This is due to multiple demographic and social factors, including women’s longer life expectancy, the spousal age gap where women often marry older spouses, and a lower likelihood of remarriage after widowhood compared to men.

Living alone for an extended period can affect older women’s physical health, psychological well-being, and economic security. On the one hand, it can foster greater resilience, autonomy, agency, and personal mastery among older women. On the other hand, it can lead to higher risks of social isolation, delayed health seeking, adverse mental health, and lower quality of life. Older women also bear a disproportionate financial burden in maintaining independent households, having accumulated fewer financial resources due to interrupted formal employment histories and lower lifetime earnings. According to Phillips (2000), poverty among older single women is potentially a critical problem linked with a high incidence of suicide among older persons.

Based on ILOSTAT (2024) data, the labour force participation rates in East Asia and the Pacific, including Southeast Asia, are 59 per cent for females and 74 per cent for males. While the global female labour force participation (FLFP) rate has remained relatively stable, the rate in East Asia and the Pacific has decreased from approximately 70 per cent in 1990 to 58.6 per cent in 2023. This decline is a concerning trend that demands urgent attention. A closer look at FLFP rates in Southeast Asia and within ASEAN countries reveals a complex picture. While the region has experienced economic growth and progress in women’s education, FLFP rates have remained relatively stagnant between 2014 and 2023, hovering around 55 per cent. This indicates a persistent challenge in facilitating women’s entry into and retention in the workforce; it also explains why a significant number of women in the region are financially unprepared to face the economic challenges of ageing. They were unable to access labour opportunities that would have enabled them to accumulate savings for retirement.

Across Southeast Asia, traditional gender roles often confine women to domestic spheres, limiting their educational and career aspirations. In the Philippines, for example, while women have high educational attainment, their labour force participation rate lags behind men’s, often due to expectations that they prioritise family caregiving, according to the Asian Development Bank (2020). Despite progress, legal frameworks in some ASEAN countries still contain discriminatory provisions that limit women’s economic opportunities.

When it comes to retirement, significant gender differences also exist. The financial needs of older women are 12 per cent higher than those of older men because of their longer life expectancy. In the case of Singapore, Choon (2008) suggests that it would be more beneficial to raise the decreed minimum sum from the Central Provident Fund—a mandatory retirement savings scheme—for older women by 6,000 Singapore dollars (compared to older men) due to their different retirement needs.

Older women’s health challenges also broadly reflect the needs of the ageing population. Women are more likely to utilise health services than men, so the differential demands may be expected to become increasingly pronounced with the shifting sex ratios, according to Hong (2000).

Policy perspectives to ensure the well-being of ageing women in Southeast Asia

How can governments ensure that their female population age well and actively? Investments for their future well-being must be made well before they reach the age of 60, and in the following critical areas:

Increased investments in women’s health, especially sexual and reproductive health.

In general, investments in research and studies on women’s health are limited. According to WEF and McKinsey Institute (2025), there is a need to conduct research into women’s health and drivers of sex-based differences, especially clinical research that focuses on conditions that affect women across their lifespan; as well as improved data collection methodologies and standards for sex- and gender-based data collection to increase understanding of women’s health. To date, studies on women-specific conditions received less than 1 per cent of cumulative research funding in 2019-2023 for all 64 conditions that drive most of the women’s health gap, including conditions that affect their lifespan such as ischaemic heart disease, cervical cancer, breast cancer, and those affecting their health span, such as migraines and menopause.

Older women, especially if they live longer than their husbands and find themselves living alone, would require specialised support in ensuring routine health maintenance while considering limited mobility as they age. One of the measures recommended by Chan et al. (2020) is to involve community-based health workers who can conduct home-based case management, coordinate appointments with health facilities, facilitate access to health screenings and diagnostic tests, and support post-hospitalisation home-based care. More investment is also needed to improve care for older women, such as studies to understand why older women are taking certain medications or why they miss them.

Select analyses of national transfer accounts (NTAs) show that the highest expenditure for women over 60 is “health,” compared to “education” for younger women. This indicates that health is the utmost priority for ageing women, but more still needs to be done to ensure accessibility and quality of care.

Targeted investments in social protection for the differentiated needs of elderly women

Countries with an increasing population of older people should focus on developing public programmes to support them, such as ensuring sustainable social security and pension systems and access to universal healthcare and long-term care. Based on their finding that older women can expect to spend a higher proportion of their lives living alone compared to older men, Chan et al. (2020) cited the need for interventions that focus on ensuring that women have the capacity and resources to live independently, particularly those that centre on improving mobility within and outside the household. Programmes need to be developed to ensure that older women living alone are socially connected and engaged and are enabled to transition between living arrangements, whether they live independently or co-reside with other family members.

Social protection plays a crucial role in ensuring that elderly women who experience specific forms of violence have access to better care and protection. It also ensures that the social workforce is equipped to address their unique needs, considering their physical and mental health, mobility issues, and potential lack of family support, particularly for unmarried or widowed women.

Countries with an increasingly older population should focus on closing the gaps in their social protection systems so that elderly women can cover increasing healthcare costs and other needs in old age and reduce their dependence on family support to sustain them for the rest of their lives.

Early investments in female labor force participation

Significant investment in female labour force participation and job creation is recommended for countries that still enjoy a rapidly growing and youthful population to prepare women for the costs of ageing, including the relevance and need for knowledgeable and skilled women in the older age bracket. Increased female labour force participation will enable women to contribute fully to pensions and social security, benefiting them in old age and lessening their dependency on income-earning family members. Being engaged in the workforce for most of their life also keeps women connected to society, potentially lessening their feelings of isolation as they age. For women to fully participate in the workforce, governments must address the caregiving obligations of women in the family, which is one of the main challenges in a woman’s ability to be gainfully employed.

Use of NTAs to inform policies that address the impact of demographic transitions, including ageing

Based on UNFPA (2023) guidance on NTAs, governments should design programmes and develop policies that take into consideration the impact of increasing numbers of certain population groups, such as younger persons or older people, on economic growth, income and employment, investment in human capital and physical capital. NTAs should provide insights on future public funding needs and a snapshot of the current situation regarding tax and welfare systems, in anticipation of an ageing society.

While NTA measures intergenerational economic flows, it is also recommended to consider the National Time Transfer Account (NTTA), which includes age and gender-specific data on the production and consumption of unpaid care and household services. NTTA includes unpaid care and domestic work, traditionally provided by women and mothers, shedding light on gender disparities in economic contributions. Such an analysis should justify greater investment in social protection and care of women in older ages, given their higher contributions to the social and economic well-being of the country through years and decades of unpaid care and domestic work.

The views and opinions in this article are solely those of the authors and do not represent the policy or official position of ASEAN.

References may be downloaded from: https://bit.ly/Issue44_Ref