A secure and satisfying job. Good income. Health care and social insurance.

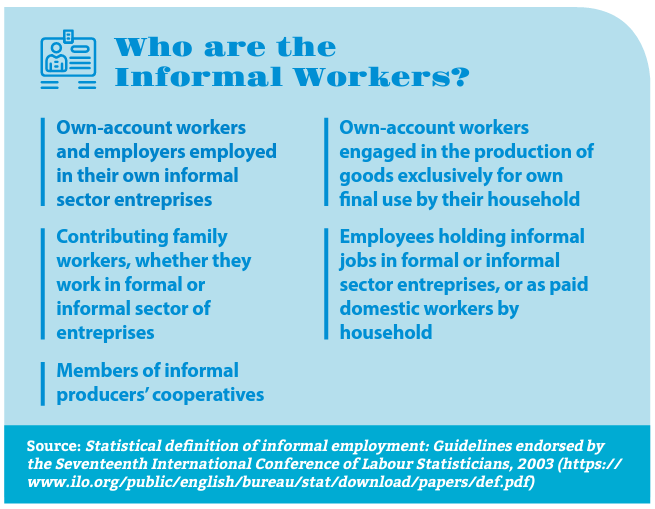

These are the bare bones expectation of every worker in ASEAN. Yet, they remain elusive for many—and more so for the informal workers in the region. In general terms, informal workers refer to people holding jobs in both formal and informal sectors who have insufficient job security, workers’ benefits, or labour and social protection.

Two new studies reveal the characteristics, vulnerabilities, and challenges faced by workers in informal employment as well as measures taken by ASEAN Member States to extend social protection to this category of workers.

Size and Characteristics of Informal Workers

Using its operational definition of informal employment, the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates ASEAN to have 244 million informal workers, representing about 80 per cent of the region’s workforce.

ASEAN Member States’ varying definitions of what constitutes “informal employment,” however, make it difficult to establish an official region-wide estimate. Cambodia and Viet Nam, for example, exclude agricultural workers, whereas Brunei Darussalam, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Thailand include them.

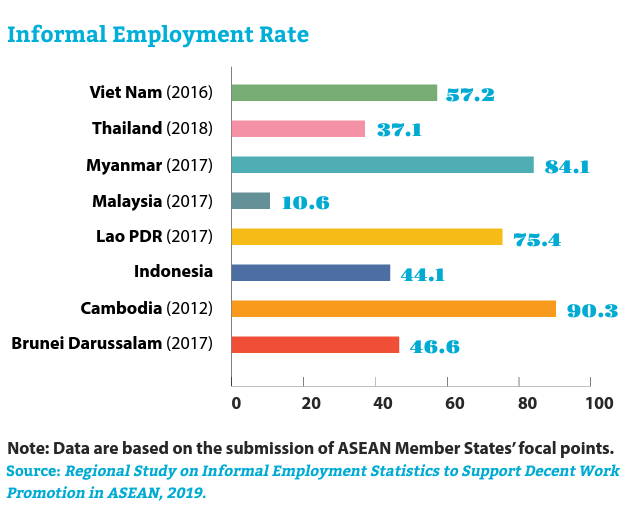

Nonetheless, on a country-by-country level, informal workers comprise a substantial portion of each Member States’ working population. In Cambodia, Myanmar, Lao PDR, and Viet Nam, informal workers account for more than half these countries’ respective workforce, with Cambodia leading the way at a high 90.3 per cent.

In the rest of Southeast Asia, the share of informal employment ranges from 10.6 per cent (Malaysia) to 46.6 percent (Brunei Darussalam). Malaysia’s low informal employment rate may be partly explained by its exclusion of workers doing informal jobs within the formal sector and those beyond 64 years old.

As expected, most informal economy workers are employed in the informal sector. But informal employment in the formal sector is also prevalent. This is the case in Cambodia and Myanmar where informal workers account for the majority of workers in the formal sector.

These figures and trends come from the Regional Study on Informal Employment Statistics to Support Decent Work Promotion in ASEAN published by the ASEAN Secretariat in 2019. The study examined existing informal employment statistics in the region and looked at how those can be translated to evidence-based policies to address informal employment. The study is part of a larger effort to fulfil ASEAN’s goals under the Vientiane Declaration on Transition from Informal Employment to Formal Employment Towards Decent Work Promotion.

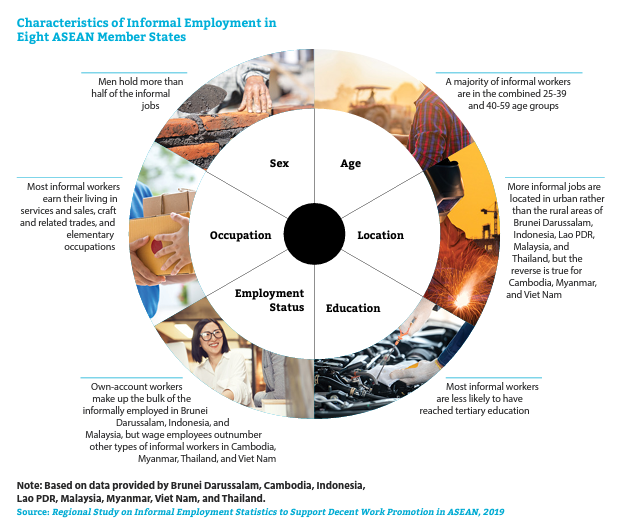

The regional study further breaks down the key characteristics of informal employment in eight of the 10 ASEAN Member States: men hold more than half of the informal jobs; a majority of informal workers are in the combined 25-39 and 40-59 age groups; most informal workers are less likely to have reached tertiary education, indicating a correlation between low educational attainment and informal employment; and most earn their living in services and sales, craft and related trades, and elementary occupations (or jobs involving simple tasks).

The regional study also looked at how Member States fare against two indicators of decent work—earnings and work hours. It notes that average earnings are higher in formal employment than informal employment. For example, Thai workers in formal employment have an average take-home pay of 23,259 Thai baht per month (or about 730 US dollars in today’s exchange rate), while those in informal employment make only about a third of that amount. There are no clear patterns when it comes to working hours. In Brunei and Cambodia, informal workers work longer, averaging about 50 hours per week, but in Indonesia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam, they work a little less or about the same number of hours per week as regular workers.

Social Protection Needs of Informal Workers

Social protection or social security, according to the ILO, encompasses all interventions that aim to prevent and reduce poverty and social exclusion of people throughout the life cycle. These include healthcare; maternity benefits; support for children and families; assistance in cases of unemployment, work-related injury, disability, or sickness; and old age and survivors’ pension.

ASEAN Member States, under the 2013 ASEAN Declaration on Strengthening Social Protection, view social protection as a basic human right that everyone is entitled to, but must especially be extended to the country’s poor, persons with disabilities, older people, out-ofschool youth, children, migrant workers, at-risk, and other vulnerable groups. Informal workers are considered to be among the most vulnerable group and in need of social protection.

The 2019 ILO study, Extension of Social Security to Workers in Informal Employment in the ASEAN Region, lays bare the specific needs and vulnerabilities of different types of workers in informal job arrangements, three of which are highlighted below.

Domestic workers are identified as among those most exposed to poor conditions and susceptible to exploitation and discrimination. Their employment terms are usually not covered by a written contract. They work for multiple employers who sometimes pay them irregularly or even make in-kind payments. They work in isolation, are not organised, and have limited or no bargaining power. In countries like Brunei Darussalam and Cambodia, the employment relationship is not recognised by law. In other countries like Malaysia and Thailand, domestic workers have limited labour protection and are not eligible to receive certain benefits, such as maternity leave and overtime pay.

Home workers—or persons who produce goods in their homes and supply them to enterprises or intermediate contractors— also have the least job security and often work in substandard conditions. Examples of these are home-based garment sewers and handicraft workers. Their work is usually labour-intensive and requires long hours, and they get compensated on a piece-rate basis. In countries where home workers may be eligible for voluntary social protection schemes such as Viet Nam, the types of benefits they can avail are confined to long-term benefits and they have to complete a qualifying period to receive pension.

Digital platform workers are an emerging class of informal workers and have yet to be covered by regulation in many countries. They include crowdworkers who accept jobs posted on global matchmaking platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk; and individuals who render on-demand services, such as transportation and food delivery, through the use of digital applications (e.g. Grab). Employment is unstable, temporary, and part-time. Platform workers are commonly treated as independent contractors rather than employees, thus releasing the intermediary platforms from the responsibility of providing workers’ benefits, such as paid leave and health insurance.

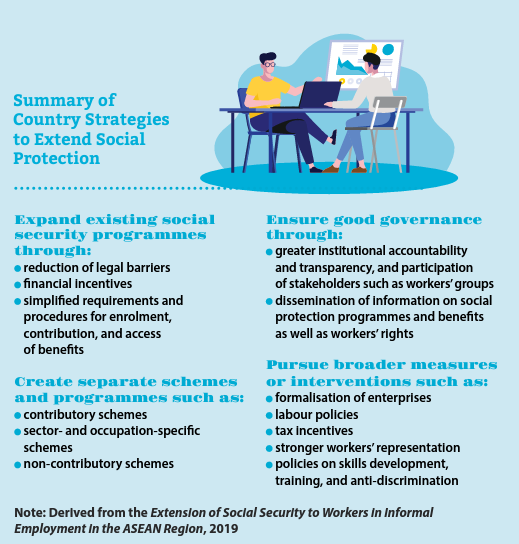

Country Strategies to Extend Social Protection

The ILO study discusses the broad spectrum of strategies and solutions that ASEAN Member States have put in place to extend social protection coverage to informal workers.

One such strategy is the expansion of existing social security programmes to accommodate the unique circumstances of informal workers. Several countries have dismantled legal barriers that previously prevented inclusion or limited the benefits of informal workers in national social security systems. In the Philippines, for example, the Domestic Workers Act of 2013 directs the inclusion of domestic workers with at least one-month employment in the country’s social security system and national health insurance, with employers paying 100 per cent of the premium contribution if the monthly salary is less than 5,000 Philippine pesos (equivalent to 101 US dollars in today’s exchange rate).

Countries are also now offering financial solutions to make it affordable for informal workers to enter into existing programmes. The Thai government, for instance, provides a counterpart amount for every contribution of workers registered under its voluntary programme (e.g. 30 baht/ month for workers contributing 70 baht/ month, which entitles workers to disability, sickness cash, and funeral benefits).

Streamlining the requirements and procedures for enroling in existing social security schemes and paying contributions is another step taken by a number of Member States. The government of Indonesia, for example, recruits community-based agents under the Kader JKN partnership programme whose tasks are to enrol new members (e.g. self-employed workers), collect contributions, disseminate information, and handle complaints. Indonesia’s national health insurance agency also developed a mobile phone app “one-stop shop” where individuals can register, update and access their data, receive information, and submit complaints.

Some Member States tried a different strategy altogether— establishing totally separate social protection programmes for uncovered groups and sectors. An example is Thailand’s National Savings Fund, an old-age insurance programme which caters to farmers, vendors, taxi drivers, daily wage earners, and self-employed workers who are not members of mandatory programmes. The Thai government matches the contribution of workers, ranging from 50 to 100 per cent, depending on the worker’s age. Another example of this strategy is Brunei Darussalam’s tax-funded universal pension programme for persons above the age of 60.

Countries are aware that social security programmes, whether existing or new, will only be successful if there are corresponding improvements in the system of governance. Thus, part and parcel of the Member States’ strategies is to make administrative processes efficient, transparent, and accessible to the public. Another is to involve workers’ and employers’ groups in designing, implementing, monitoring and evaluating social protection programmes.

Member States are also pursuing broader, non-social security strategies that indirectly affect informal workers’ access to social insurance. One of these is the business registration or formalisation of informal enterprises which will make it compulsory for employers to enrol their workers in social protection programmes. Another is the provision of tax incentives such as the tax deductions offered by Singapore to self-employed workers who are enroled in its Medisave and Central Provident Fund programmes. Measures that promote workers’ organisation and representation, create opportunities for training and skills development of workers, and end discrimination are also being carried out.

Agenda for Action

The two informal employment studies cited areas for action at both country and regional levels.

ASEAN’s regional study on informal employment statistics urges countries to strengthen their national database on informal employment by, among others, regularly conducting labour force surveys; create an inter-agency committee on informal employment statistics to set clear directions on data collection and analysis; improve country analysis and reporting of informal employment statistics; and institutionalise use of informal employment data by including these in the computation of national income accounts. It also proposes that countries establish an official operational definition of informal employment and determine the classification of platform workers.

At the regional level, the ASEAN study recommends the establishment of a regional database, using the study’s varying statistical tables on informal employment as a starting point, and to build on this database by including additional indicators like occupational safety, health, and decent work indicators, to name a few. Following this recommendation, the ASEAN Secretariat has incorporated informal employment statistics tables in the ASEAN Statistics Web Portal.

The ILO study, meanwhile, gave a number of recommendations that some ASEAN Member States have already put in place, including strengthening the coordination among relevant agencies and at different levels of government; subsidising the participation of low-income workers in social protection programmes; identifying and eliminating legal impediments to informal workers’ coverage; and simplifying administrative procedures and delivery mechanisms.

Additionally, it advises governments to be responsive to the expressed need of uncovered groups in developing social insurance programmes (e.g. preference for short-term rather than long-term benefits), and address as well the problematic areas of ongoing programmes, such as adverse selection and low participation in voluntary contribution schemes.

Finally, the ILO study encourages Member States to increase their investment in social protection, develop evaluation and monitoring tools for assessing country and regional progress, and strengthen ASEAN-level collaboration in the areas of knowledge-sharing, capacity-building, technical assistance, and pilot projects.